The super-rich have opened their wallets to Modi, and income inequality has soared over the past decade. With an election coming, ordinary voters need to ask, ‘What’s in it for us?

India’s soaring income inequality is now among the highest in the world. The gap between the haves and have-nots is starker than in the US, Brazil and South Africa, and worse than in the country’s own history under foreign rule. So here’s a question for political scholars: With the dice so badly loaded against them, why would 1 billion voters prefer to make the rich even richer when they exercise their democratic choice in April and May? What’s in it for them?

“The ‘Billionaire Raj’ headed by India’s modern bourgeoisie is now more unequal than the British Raj headed by the colonialist forces,” says a new study by the World Inequality Lab. The report, which spans a century, shines a spotlight on 2014-2022, the first eight years of rule by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his right-wing Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, or BJP.

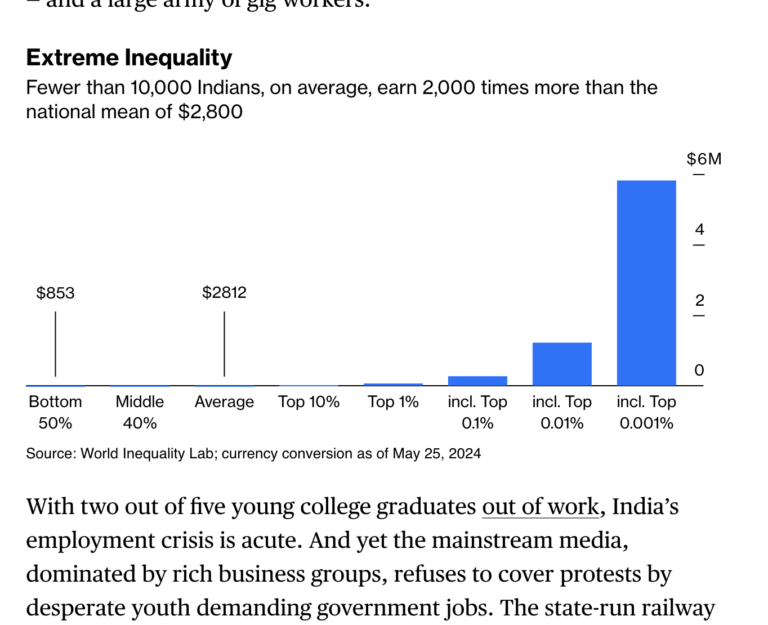

With Modi seeking a third term in the upcoming general elections, the researchers corroborate something that’s been evident to economists for some time. While inequality has grown since the 1980s, in step with a lopsided distribution of gains from globalization across the world, Modi’s reign has spawned a tiny class of super-rich. Fewer than 10,000 individuals in a population of 920 million adults earn an average 480 million rupees ($5.7 million), more than 2,000 times the average income of $2,800. Nine out of 10 Indians earn less than the average.

The Modi years have been exceptionally generous to the affluent. Those at the very top of the pyramid saw their real income double. That surge has been four times faster than the growth enjoyed by the median earner. At the 99.99% percentile mark of the distribution, wealth increased by 175%, compared with 50% at the midpoint.

A handful of tycoons — such as Mukesh Ambani, Gautam Adani and Sajjan Jindal — have entered the leagues of the world’s richest people. They did so not by putting innovative products and services in global markets, but by carving up domestic industries such as transportation, telecom, power and gas, metals, retail, media and new energy. The Modi government rewarded large businesses with tax cuts and awarded them prized monopoly assets like airports. The billionaires got juicy deals when buying bankrupt firms and lobbied — often successfully — for protectionist trade policies. At the same time, India’s rules on foreign direct investment protected the national team from muscular global rivals.

None of this trickled down to workers. The share of manufacturing, which could have created jobs for the bulging youth population, has shrunk to 13% of the overall output, compared with 28% in China. This is despite $24 billion in subsidies for investors putting up factories to cut their reliance on the People’s Republic. Real, or inflation-adjusted, wages have been stagnant for a decade. Startups mushroomed as a result of digitization and cheap money during the pandemic. But they only created a tiny cohort of paper billionaires — and a large army of gig workers.

Extreme Inequality

Fewer than 10,000 Indians, on average, earn 2,000 times more than the national mean of $2,800

Source: World Inequality Lab; currency conversion as of May 25, 2024

With two out of five young college graduates out of work, India’s employment crisis is acute. And yet the mainstream media, dominated by rich business groups, refuses to cover protests by desperate youth demanding government jobs. The state-run railway network is badly understaffed. Regular army recruitment has been replaced by tours of duty from which 75% of soldiers would be demobilized after four years, a sorry experiment that might only produce combat-trained mercenaries for global warfare and security guards for the private sector. Young people are lining up for jobs in Israel, or getting lured by agents to fight in the Russia-Ukraine war. Farmers are restive about unviability of crop production amid rapid climate change.

Still, the average voter doesn’t seem to care about the economic squeeze. Or at least that’s what the numbers suggest.

In 2019, when Modi sought his first reelection, the BJP’s vote share increased to 37%, a six-percentage-point increase from five years earlier. (In India’s first-past-the-post system, the vote share of the BJP or the Congress Party, the main opposition, hasn’t exceeded 40% in any election since 1984.) A third term for Modi is the central forecast of nearly every analysis of the upcoming polls.

The rich have funneled $1.5 billion to the BJP — 58% of all known political funding since 2018 — according to an analysis by a consortium of media organizations and independent journalists. It’s reasonable to assume that the wealthy are seeking to advance their interests. A chunk of these donations, transferred anonymously via bearer bonds, is currently causing grief to the government and its backers. The Supreme Court has declared the bonds as unconstitutional and forced disclosures, despite all efforts by the state and business interests to keep voters from knowing who gave money to whom.

But the discomfiture of the rich is not the issue. What’s more worrying is their cynical confidence. They seem to believe that the broader electorate has been so polarized along religious lines that voters won’t care about even the most egregious quid pro quo between politics and business. After all, the poor are receiving some state funds in their bank accounts as subsidies for shelter, cooking gas, and toilets. Almost 800 million Indians are now on a monthly ration of free food — and a daily dose of bigotry targeted at the 14% of the population who are Muslims.

This will be the first national election since the V-Dem Institute, an independent research unit at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, classified India as an “electoral autocracy” in 2021. The downgrading of the world’s largest democracy couldn’t have been possible without the billionaires. They can probably look forward to a crazy stock-market rally after a Modi win.

A ninth straight year of gains in benchmark indexes will attract both domestic savings and global liquidity. This is important because when you consider the top 10% of population, the Chinese are slightly ahead of Indians — in control of 70% of national wealth, according to the inequality report co-authored by New York University economist Nitin Kumar Bharti, Harvard Kennedy School’s Lucas Chancel, and Paris School of Economics’ researchers Thomas Piketty and Anmol Somanchi.

Once 100 million adults establish a similar stranglehold on affluence in Modi’s India, the oligarchs may be in complete control of the nation’s political narrative — and its economic destiny.

Excerpts: Bloomberg 26 March 2024

Andy Mukherjee is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies and financial services in Asia. Previously, he worked for Reuters, the Straits Times and Bloomberg News

COMMENTS