My newsroom colleagues Jason Horowitz and Gaia Pianigiani have a lovely report this week about family-friendly policies in the Italian province of Alto Adige-South Tyrol, which has the highest birthrate of any region in an aging, depopulating Italy.

Their story is a portrait not just of a particular policy matrix but also the culture that policy can help foster. In particular, it highlights the extent to which the province offers not just direct funding for parents — for the family with six kids profiled in the story, that means 200 euros a month for each child until they turn 3, on top of the family benefits offered by Italy’s national government — but also a more comprehensive attempt to build a child-friendly social order. The province’s parents “enjoy discounted nursery schools, baby products, groceries, health care, energy bills, transportation, after-school activities and summer camps.” Teachers are encouraged “to turn their apartments into small nurseries,” workplaces offer breastfeeding breaks, and one workplace lobby is filled with “fliers advertising ‘Welcome Baby’ backpacks loaded with tips for new parents and picture books.”

As a portrait of a family-friendly exception to a larger anti-natal rule, the story dovetails with arguments in a new book from Tim Carney of The Washington Examiner, “Family Unfriendly: How Our Culture Made Raising Kids Much Harder Than It Needs to Be,” which focuses on the ways that American society conspires to make parenting seem incredibly high-effort, well-nigh impossible.

Some of what Carney describes is a set of habits that’s beyond the reach of policy. (I don’t think there’s much the government can do to persuade parents to “Have Lower Ambitions for Your Kids,” to select one of his more striking chapter titles.) But some of the sense of overwhelmingness that comes with modern parenting seems like it could be mitigated, not just through a once-a-year benefit or tax credit, but also through small consistent signals of support: the family discount on groceries, the convenient in-home child care option, the open play space, the flexible work space.

If the developed world isn’t going to disappear into a gray and underpopulated future, there needs to be some “change in the overall ethos and structure of parenting,” as my Opinion colleague Jessica Grose put it last year, some rewiring of both parental and societal expectations — a rewiring that one Italian province, in my colleagues’ account, seems to have partly achieved.

But emphasize that “partly.” Last week, The Financial Times’s data maven, John Burn-Murdoch, ran a story under the headline “Why family-friendly policies don’t boost birthrates.” That claim seems to conflict with the lessons of Alto Adige-South Tyrol, but really what Burn-Murdoch meant wasn’t that such policies have no effect at all. It’s just that they don’t seem to boost birthrates enough to make up for whatever social and cultural and economic forces keep pushing them below replacement and then even lower still.

And that’s what you see in the Italian example. My colleagues mention that attempts at family-friendly policymaking in the neighboring province of Trentino, which borders Alto Adige-South Tyrol to the south, have been more disappointing: “Its birthrate has nevertheless plunged to 1.36 children per woman,” which is “much closer to the dismal national average.” This is true, but it’s also true that a birthrate of 1.36 is higher than in any other region in Italy.

So Trentino’s efforts are a failure in the sense that they haven’t matched their neighbor’s more impressive results or prevented stark decline. But maybe they’re also a success relative to the no-policy alternative, a case study in how family-friendly efforts make an important difference at the margin even if they can’t simply overcome larger trends.

What might actually overcome those trends? The harsh answer for the moment appears to be, well, nothing. But a more optimistic answer would reach for some larger idea of meaning and mission as the thing that low-birthrate cultures need to somehow recover.

Part of the explanation for the special fecundity of Alto Adige-South Tyrol, my colleagues suggest, lies in its particular heritage as a Germanic enclave absorbed into the Italian republic, which may instill a special interest in its own cultural survival. Likewise, Carney’s book discusses the Israeli exception to the general rule of rich societies having below-replacement birthrates — an exception that includes secular Israelis as well as the ultra-Orthodox and clearly has something to do with a sense of national mission that the Israeli experiment retains. And another new book, “Hannah’s Children: The Women Quietly Defying the Birth Dearth,” from Catherine Ruth Pakaluk at the Catholic University of America, looks at a different exceptional group, American women having five or more kids, and finds a similar sense of mission, usually religious, as their defining commonality. (I should note that I’ll be moderating a conversation with Pakaluk and Carney at Catholic University in Washington on the evening of April 29.)

How you would translate this sense of mission from the smaller to the larger scale, from small regions and countries and particularly religious cohorts to mass societies, is a question whose lack of obvious answers leads us back to pessimism. At the very least it’s clear that any sweeping kind of fertility recovery would have to defy current expectations and integrate structures of meaning, habits of family formation and modern lifestyles in a way that nobody can quite see coming yet.

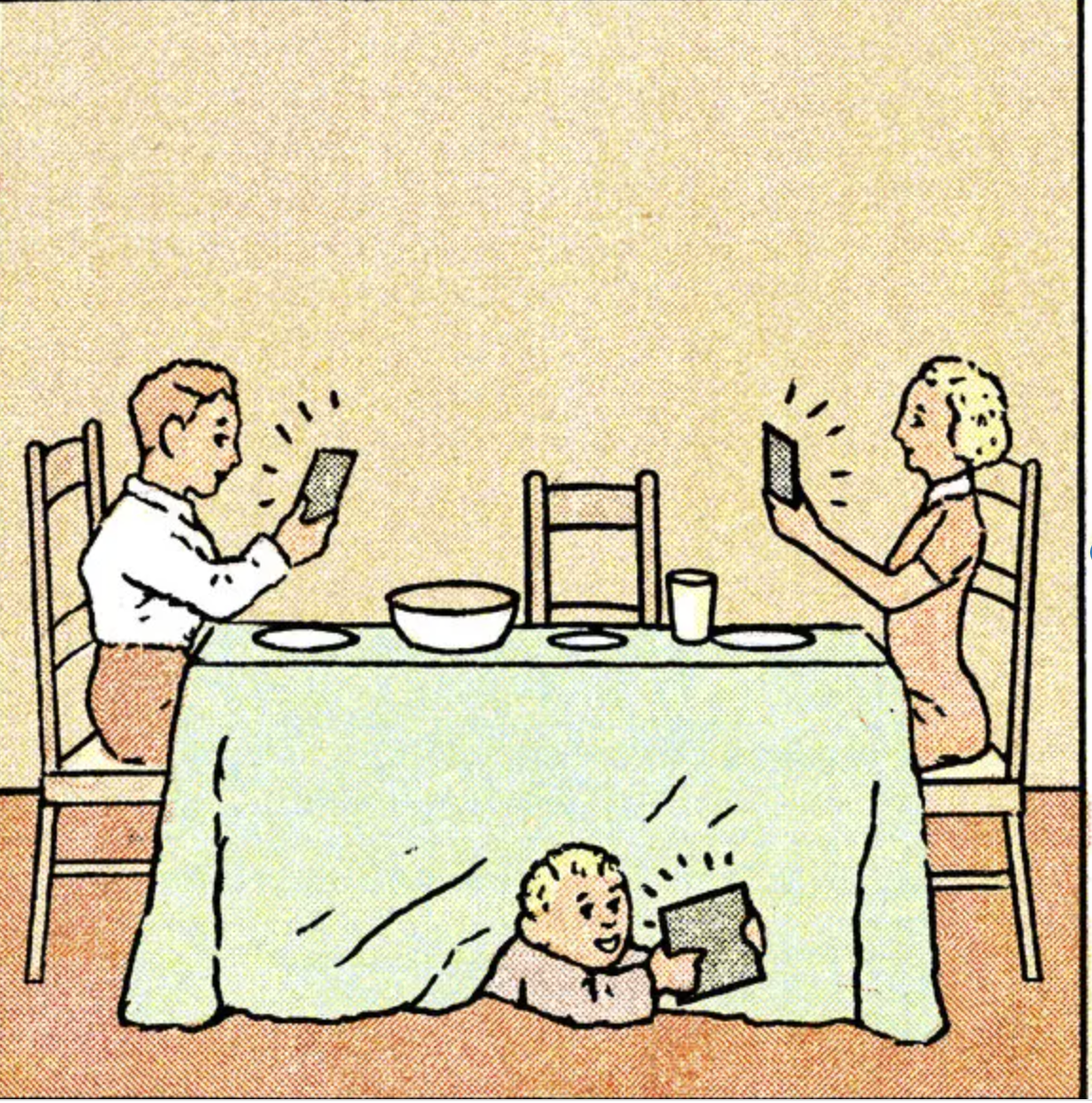

Which brings me to smartphones. One of the best reviews of Carney’s book, from Leah Libresco Sargeant in First Things, pairs it with Jonathan Haidt’s “The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness,” about the effect of phones and screens and social media on childhood and adolescence. Carney’s book has a discussion of the screen world’s negative effects on family life, and Haidt’s book offers a portrait of what’s gone wrong with Western childhood in the smartphone age, the loss of independence and unscheduled play and face-to-face interactions between kids, that would be fully at home in “Family Unfriendly.”

Uniting these accounts, Sargeant makes the point that screens have arguably become a substitute for better forms of family friendliness, a way of managing kids in a society that doesn’t want to really deal with all their disruptive energy, their irreducible non-adultness. It’s a new way of making them seen and not heard, or neither seen nor heard: “A child stooped over a phone,” after all, “is quiet, nondisruptive, and doesn’t have to be in public at all.” If screens are possibly making them unhappier, they’re also making them more tractable in a way that substitutes for any larger social transformation that might make them welcome.

We talked about Haidt’s book a bit on our Times Opinion podcast this week, and there’s much more to say about his argument and the critiques that it has generated. But let’s stay with this question of how screens help manage childhood.

All my biases make me agree with the anti-smartphone case, and indeed my strong suspicion is that the culture smartphones create among not just kids but also 20-something adults helps explain the acceleration of the fertility decline in recent years. But because those are my biases, it’s useful to push against them. So consider a different read on Sargeant’s argument: If screens make kids more manageable, shouldn’t they potentially make it easier to have and rear them?

Yes, in this timeline, their use is often intertwined with helicopter parenting and obsessive achievement culture, and may feed into anti-child tendencies in the wider social landscape. But just as a bare fact of parental life, an iPad really can make a long family trip or plane ride much more bearable for a beleaguered mom or dad. A family network of phones really can make it easier to juggle the responsibility for multiple kids and all their play dates and activities. There really are times when it’s OK for kids to be seen but not heard and for streaming entertainment to play a crucial role in letting a parent get dinner on the table.

Likewise for adults and their screens. My phone distracts me from my kids, it sets a bad example for them, but it also makes it possible for me to be present in all kinds of important ways, even when I have work obligations. Remote work seems to make it easier to have kids and to live in houses and neighborhoods that give them space, to escape the potentially fertility-crushing effects of urban density. The internet makes it easier to encourage eccentric childhood interests, to run a home-schooling cooperative, to connect with grandparents in distant states and more.

In our podcast discussion, I was perhaps a bit more optimistic than my co-hosts about our capacity to create a more smartphone-free form of childhood. But I will concede that we are not going to build a smartphone-free society on any non-apocalyptic timeline.

So to imagine a transformed culture that’s friendlier to families and more welcoming to kids is necessarily to imagine one that employs screens in all kinds of ways, but with a mastery over their effects and an intentionality about their uses that we have not yet been able to achieve.

Breviary

Jonathan Haidt and Tyler Cowen in friendly combat.

Bryan Garsten on liberalism as a refuge.

Jessica Winter on liberalism as a meltdown.

Matthew Rose on the radical right.

Noah Smith on the incentives of euthanasia.

Was the “Seinfeld” finale actually good?

The library of Nayib Bukele.

This Week in Decadence

— Derek Thompson, “The True Cost of the Churchgoing Bust,” The Atlantic (April 3)

… America didn’t simply lose its religion without finding a communal replacement. Just as America’s churches were depopulated, Americans developed a new relationship with a technology that, in many ways, is the diabolical opposite of a religious ritual: the smartphone. As the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt writes in his new book, “The Anxious Generation,” to stare into a piece of glass in our hands is to be removed from our bodies, to float placelessly in a content cosmos, to skim our attention from one piece of ephemera to the next. The internet is timeless in the best and worst of ways — an everything store with no opening or closing times. “In the virtual world, there is no daily, weekly, or annual calendar that structures when people can and cannot do things,” Haidt writes. In other words, digital life is disembodied, asynchronous, shallow and solitary.

Religious rituals are the opposite in almost every respect. They put us in our body, Haidt writes, many of them requiring “some kind of movement that marks the activity as devotional.” Christians kneel, Muslims prostrate and Jews daven. Religious ritual also fixes us in time, forcing us to set aside an hour or day for prayer, reflection or separation from daily habit. (It’s no surprise that people describe a scheduled break from their digital devices as a “Sabbath.”) Finally, religious ritual often requires that we make contact with the sacred in the presence of other people, whether in a church, mosque, synagogue or over a dinner-table prayer. In other words, the religious ritual is typically embodied, synchronous, deep and collective.

… Finding meaning in the world is hard too; it’s especially difficult if the oldest systems of meaning-making hold less and less appeal. It took decades for Americans to lose religion. It might take decades to understand the entirety of what we lost.

Advertisements for Myself

I will be participating in two debates next week: Arguing the negative for the proposition “Is Assisted Dying Moral?” at Stanford University on Tuesday, April 9 at 5 p.m., and moderating a debate on campus free speech amid the Israel-Hamas war, in Cambridge, Mass., on Thursday, April 11 at 7 p.m. Both events are free but require registration.

Excerpts: The New York Times

COMMENTS