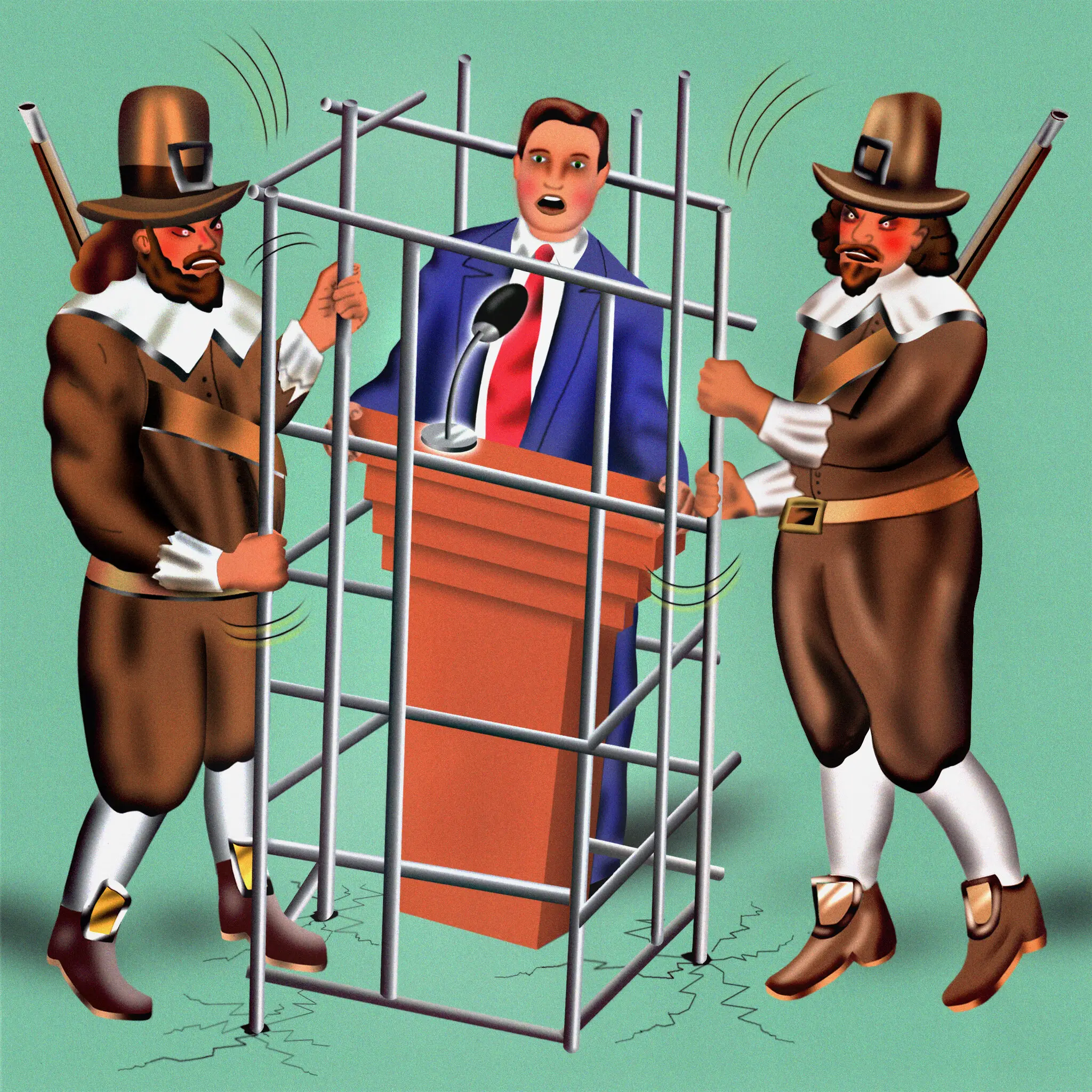

The yet-to-be-president holds forth on strength, friendship, dealmaking, public service and building violations.

One evening in February 1989, my Watergate reporting partner Carl Bernstein bumped into Donald Trump at a dinner party in New York.

“Why don’t you come on up?” Carl urged me on the phone from the party, hosted by Ahmet Ertegun, the Turkish American socialite and record executive, in his Upper East Side townhouse. “Everybody’s having a good time,” he said. “Trump is here. It’s really interesting. I’ve been talking to him.”

Carl was fascinated with Trump’s book, “The Art of the Deal.” Somewhat reluctantly, I agreed to join him, in large part, as Carl often reminds me, because I needed the key to his apartment, where I was staying at the time.

“I’ll be there soon,” I told him.

It had been 17 years since Carl and I first collaborated on stories about the Watergate burglary on June 17, 1972.

Trump took a look at us standing together, and he came over. “Wouldn’t it be amazing if Woodward and Bernstein interviewed Donald Trump?” he said.

Carl and I looked at each other.

“Sure,” Carl said. “How about tomorrow?”

“Yeah,” Trump said. “Come to my office at Trump Tower.”

“This guy is interesting,” Carl assured me after Trump was gone.

“But not in politics,” I said.

I was intrigued by Trump, a hustler entrepreneur, and his unique, carefully nurtured persona, designed even then to manipulate others with precision and a touch of ruthlessness.

The Trump interview, taped on a microcassette, transcribed and printed, was deposited into a manila envelope with a copy of Trump’s book and eventually lost in piles and piles of records, interview notes and news clippings. I am a pack rat. For over 30 years, Carl and I looked for it.

I joked with President Trump about “the lost interview” when I interviewed him in the Oval Office in December 2019 for the second of my three books on his presidency, “Rage.”

“We sat at a table and we talked,” Trump recalled. “I remember it well.” He said I should try to find it because he believed it was a great interview.

Last year, I went to a facility where my records are stored and sifted through hundreds of boxes of old files. In a box of miscellaneous news clippings from the 1980s, I noticed a plain, slightly battered envelope — the interview.

It’s a portrait of Trump at age 42, focused on his real estate deals, making money and his celebrity status. But he was hazy about his future.

“I’m really looking to make the greatest hotel,” Trump told us in 1989. “That’s why I’m doing suites on top. I’m building great suites.

“You ask me where I’m going, and I don’t think I could tell you at all,” Trump said. “If everything stayed the way it is right now, I could probably tell you pretty well where I’m going to be.” But, he emphasized, “the world changes.” He believed that was the only certainty.

Woodward What’s going to be the second act or the third act?

He also spoke about how he behaved differently depending on whom he was with. “If I’m with fellas — meaning contractors and this and that — I react one way,” Trump said. Then he gestured to us. “If I know I have the two pros of all time sitting there with me, with tape recorders on, you naturally act differently.”

“Much more interestingly would be the real act as opposed to the facade,” Trump said about himself. I wondered about “the real act.”

“It’s an act that hasn’t been caught,” Trump added.

Story continues below advertisement

He was constantly performing, and, that day, we were the recipients of his full-on charm offensive.

“It’s never the same when there’s somebody sitting with you and literally taking notes. You know, you’re on your good behavior, and frankly, it’s not nearly as interesting as the real screaming shouting.”

Trump also appeared preoccupied with looking tough, strong.

“The worst part about the television stuff when we do it is they put the makeup all over you,” Trump said. “This morning I did something and they put the makeup all over your face and so do you go up and take a shower and clean it off or do you leave it? And in the construction business, you don’t wear makeup. You got problems if you wear makeup.”

Woodward On Watergate, one of Carl’s favorite quotes was John Mitchell’s quote,

We asked Trump to take us through the steps of one of his real estate deals. How are they done?

“Instinctively, I know exactly,” he said immediately. “I cannot tell you what it is, you understand. Because instinct is far more important than any other ingredient if you have the right instincts. And the worst deals I’ve made have been deals where I didn’t follow my instinct. The best deals I’ve made have been deals where I followed my instinct and wouldn’t listen to all of the people that said, ‘There’s no way it works.’

“Very few people have proper instincts,” he said. “But I’ve seen people with proper instincts do things that other people just can’t do.”

Is there a master plan?

“I don’t think I could define what the great master plan is,” he said, referring to his life. “You understand that. But it somehow fits together in an instinctual way.”

Trump To me, it’s all very interesting.

I asked about his social conscience. Could it “lead you into politics or some public role?”

“To me, it’s all very interesting,” he said. “The other week, I was watching a boxing match in Atlantic City, and these are rough guys, you know, physically rough guys. And mentally tough in a sense, okay. I mean, they’re not going to write books but mentally tough in a certain sense.

“And the champion lost and he was defeated by somebody who was a very good fighter but who wasn’t expected to win. And they interviewed the boxer after the match, and they said, ‘How’d you do this? How’d you win?’

“And he said, ‘I just went with the punches, man. I just went with the punches.’ I thought it was a great expression,” Trump said, “because it’s about life just as much as it is about boxing or anything else. You go with the punches.”

To look back over Trump’s life now — his real estate deals, presidency, impeachments, investigations, civil and criminal trials, conviction, attempted assassination, campaign for reelection — that is exactly what he has done. Go with the punches.

“People ask me and they might ask you guys, you know, where are you going to be in 10 years? I think anybody that says where they’re going to be is a schmuck,” Trump added. “The world changes. You’ll have depressions. You’ll have recessions. You’ll have upswings. You’ll have downswings. You’ll have wars. Things that are beyond your control or in most cases beyond people’s control. So you really do have to go with the punches and it’s bad to predict too far out in advance, you know, where you’re going to be.”

At the time, he was almost obsessed with critical news headlines about him losing deals.

“You make more money as a seller than you do as a buyer,” Trump explained. “I found that to be a seller today is to be a loser. Psychologically. And that’s wrong.

“I’ll tell you what. I beat the s— out of a guy named Merv Griffin,” Trump said. Griffin was a television talk show host and media mogul. “Just beat him. And, you know, he came in — you talk about makeup. He came in with makeup and he was on television, you know, he comes into my office. He made a deal to buy everything I didn’t want in Resorts International,” Trump said. “I kept telling him no, no, no, no, and he kept raising the price, raising the price, raising the price. All of a sudden, it turns out to be an incredible deal for me. An unbelievable deal.

“Plus,” Trump added, “I got the Taj Mahal, which is the absolute crown jewel of the world.” He was referring to the Taj Mahal casino in Atlantic City, not the sacred mausoleum in India.

“The point is that people thought I lost,” he said. “So what’s happened is there’s a mood in the world for the last five years that if you’re a seller, you’re a loser, even if you’re a seller at a huge profit.”

I asked Trump, when you get up in the morning, what do you read? Whom do you talk to? What information sources do you trust?

“Much of it is very basic,” Trump said. “I read the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times. I read the Post and the News, not so much for business, just to sort of I live in the city and you know, it’s reporting on the city.” The New York Post covered Trump almost obsessively.

“I rely less on people than I do just this general flow of information,” he said. “I also speak to cabdrivers. I go to cities and say, what do you think of this? That’s how I bought Mar-a-Lago. Talking to a cabdriver and asking him, ‘What’s hot in Florida? What’s the greatest house in Palm Beach?’”

“Oh, the greatest house is Mar-a-Lago,” the cabdriver said.

“I said where is it? Take me over.” Trump then added, “I was in Palm Beach, I was in the Breakers, and I was bored stiff.”

Trump eventually bought Mar-a-Lago for $7 million.

“I talk to anybody,” he said. “I always call it my poll. People jokingly tell me you know that Trump will speak with anybody. And I do, I speak to the construction workers and the cabdrivers, and those are the people I get along with best anyway in many respects. I speak to everybody.”

Trump What happened in Bally was sort of interesting.

Trump claimed he bought 9.9 percent of a casino company, Bally Manufacturing, and in a short period of time made $32 million. He then said he spent “close to 100 million dollars on buying stock” in Bally, which led to a lawsuit against him. The lawyers for the other side wanted Trump’s records.

“They were trying to prove that I did this tremendous research on the company, that I spent weeks and months analyzing the company,” Trump said. “And they figured I’d have a file that would be up to the ceiling. So they subpoenaed everything, and I end up giving them virtually no papers. There was virtually no file. So I’m being grilled, you know, so-called grilled by one of their high-priced lawyers.”

Trump impersonated the lawyer: “How long did you know about this, Mr. Trump? And when?”

“In other words, they’re trying to say like this is this great plot,” Trump said. “I said, I don’t know, I just started thinking about it like the day I bought it.”

The lawyer was incredulous. “Well, how many reports did you do?”

“Well, I really didn’t, I just sort of had a feeling.”

“They didn’t believe that somebody would take 100 million bucks and put it into a company with virtually no real research,” Trump said. “Now I had research in my head, but beyond, you know, they just had not thought that happens. And the corporate mind and the corporate mentality doesn’t think that happens. Those are my best deals.”

Carl asked Trump whether he ever sees himself in a public service role.

“I don’t think so, but I’m not sure,” Trump said. “I’m young. In theory, statistically, I have a long time left. I’ve seen people give so much away that they don’t have anything when bad times come.”

He said he was setting up a Donald J. Trump Foundation. “When I kick the bucket — as the expression goes — I want to leave a tremendous amount of money to that foundation. Some to my family and some to the foundation. You have an obligation to your family.”

Trump spoke about “bad times” as if they were inevitable. “I always like to sort of prepare for the worst. And it doesn’t sound like a very particularly nice statement,” he said. “I know times will get bad. It’s just a question when.”

He brought up his 281-foot yacht, which was originally owned by Saudi businessman and arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi. Trump had renamed it Trump Princess. “To build new today would cost 150 to 200 million dollars. If you guys want, we’ll go on it or something. … It’s phenomenal. If you read Time magazine, I do nothing but float around on this boat all day long. It’s not the way it is.”

Woodward Who do you consider your best friend?

Who is your best friend? I asked.

He listed some names of businessmen and investors, people who worked for him, that neither Carl nor I recognized, and his brother Robert. “In, I guess all cases, business-related,” he said. “Only because that’s the people I deal with.”

“But friendship is a strange thing. You know, I’m always concerned with friendship because I’ve seen — sometimes you’d like to test people. Right now everybody wants to be my friend for whatever reason. Okay, for the obvious reasons.

“Sometimes you’d like to test them and say one day, just for a period of a week, that Trump blew it. And then go back and call ’em up and invite ’em to dinner and see whether or not they show up. I’ve often wanted to do that. Take a period of a month and let the world think that I blew it just to test whether or not in fact the friends were friends.”

“I’m a great loyalist. I believe in loyalty to people. I believe in having great friends and great enemies. And I’ve seen people who were on top who didn’t stay on top and all of a sudden the same people that were kissing their a– are gone. I mean like gone.

“One example was a banker. He was really a great banker, for one of the big banks — Citibank. And he was in charge of huge loans to very substantial people.

“He made a lot of people rich loaning money and he called me like two years after the fact. He said, you know, it’s incredible, the same people that were my best friends, that were calling me up all the time and kissing my a– in every way, I can’t even get through to ’em on the telephone anymore. … When he left the bank, they wouldn’t take his calls anymore.

“I would.”

Trump described his strategy of refusing to pay fines for the violations he received from property inspectors.

“From day one, I said f— them,” Trump said of the inspectors.

“When I was in Brooklyn, inspectors would come around and they’d give me a violation on buildings that were absolutely perfect,” Trump recalled. “I’d say, ‘F— you.’ And they’d give me more violations. And more. And for one month it was miserable. I had more violations — and they were unfounded violations. But they give it because what they wanted was if you ever paid ’em off, they’d always come back. So what happened to me, in one month they just said, ‘F— this guy, he’s a piece of s—.’ And they’d go to somebody else.”

“The point is if you fold, it causes you much more trouble than it’s worth,” Trump said.

“You can say the same thing with the mob. If you agree to do business with them, they’ll always come back. If you tell ’em to go f— themselves — in that case, perhaps in a nicer way. But if you tell them, ‘Forget it, man, forget it, nothing’s worth it,’ they might try and put pressure on you at the beginning but in the end they’re going to find an easier mark because it’s too tough for them. Inspectors. Mobs. Unions. Okay?”

This was Trump’s basic philosophy.

Carl asked, who are your greatest enemies?

“Well, I hate to say because then you’re just going to go and interview ’em. I hate playing the role of a critic.”

Trump in fact loved it. “The obvious one is Ed Koch,” he said. “Ed Koch was the worst mayor in the history of New York City.”

Thirty-five years later, Trump still criticizes opponents with the same exaggerated effect. “Joe Biden is the worst president in the history of the United States,” he said after President Biden announced in July that he would not be seeking reelection.

Even in 1989, Trump’s character was focused on winning, fighting and surviving. “And the only way you do that,” he said, “is instinct.”

“If people know you’re a folder,” he said, “if people know that you’re going to be weak, they’re going to go after you.”

Trump said it was “a whole presentation.”

Trump It’s a whole presentation.

“You’ve got to know your audience, and by the way, for some people, be a killer, for some people, be all candy. For some people, different. For some people, both.”

Killer, candy or both. That’s Donald Trump.

What a remarkable time capsule, a full psychological study of a man, then a 42-year-old Manhattan real estate king.

I never expected Trump to become president or a defining political figure of our time. The same instincts I reported on during his presidency were just as much a trademark of his character back in 1989. Here, in this interview 35 years ago, we see the origin of Trumpism in the words of Trump himself.

Excerpted washingtonpost. from “War” by Bob Woodward. Copyright © 2024 by Bob Woodward.

Bob Woodward is an associate editor of The Washington Post, where he has worked since 1971.

Education: Yale UniversityBob Woodward is an associate editor of The Washington Post, where he has worked since 1971. He has shared in two Pulitzer Prizes, first in 1973 for the coverage of the Watergate scandal with Carl Bernstein, and second in 2003 as the lead reporter for coverage of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. He has authored or coauthored 18 books, all of which have been national non-fiction bestsellers. Twelve of those have been #1 national bestsellers. His most recent book, The Last of the President’s Men, was published by Simon & Schuster in 2015. Bob Schieffer of CBS News has said, “Woodward has establish.

COMMENTS