The economic crisis of the 1970s was a disaster for multiple presidents. It could be worse for Trump.

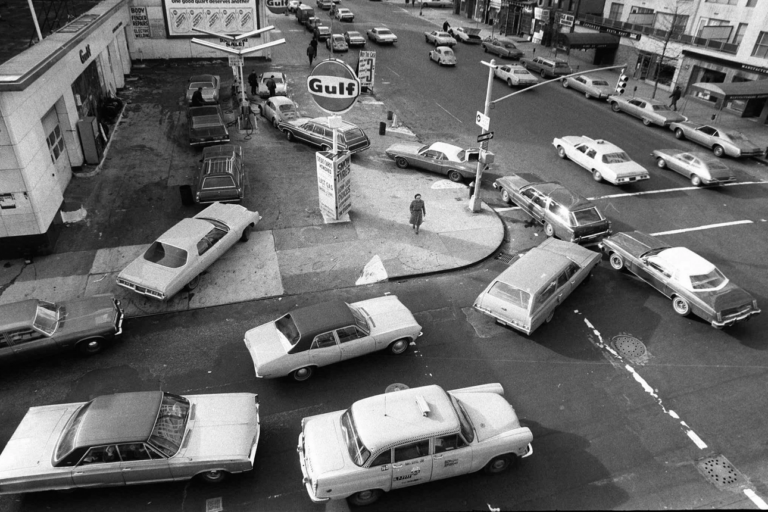

Cars line up in two directions at a gas station. Cars wait in a long line at a gas station in New York City, in December 1973. | Marty Lederhandler/AP

In the leadup to President Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day” on Wednesday — when he announced sweeping new tariffs on all the United States’ international trading partners — economists and financial analysts started using a word that will give hives to those of you over the age of 60.

Stagflation — “the s-word rippling through Wall Street and Main Street,” as Axios put it earlier this week — is a calamitous anomaly whereby the economy manifests low growth and high inflation at the same time. Anyone who remembers the 1970s will recall that it caused an economic crisis in the United States, ushering in a turbulent era of high prices, interest rates and unemployment — and considerable instability and pain.

Today, experts are worried that Trump’s new tariff regime — which is all but certain to raise prices — coupled with a tight labor market could return us to that era. As a researcher at Deutsche Bank recently observed, “The data is continuing to support the narrative of weaker growth and higher inflation, with market-based inflation expectations continuing to rise.” And on Sunday, Richard Clarida, a former vice chair of the Federal Reserve who now advises the Pacific Investment Management Company, told Bloomberg that he already sees a “whiff of stagflation” in the economy.

That’s not just a financial risk for the American people — history indicates it’s also a potentially existential political problem for Trump.

A trader works on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange during morning trading on April 3, 2025, the day after President Donald Trump’s announcement of new sweeping tariffs. | Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

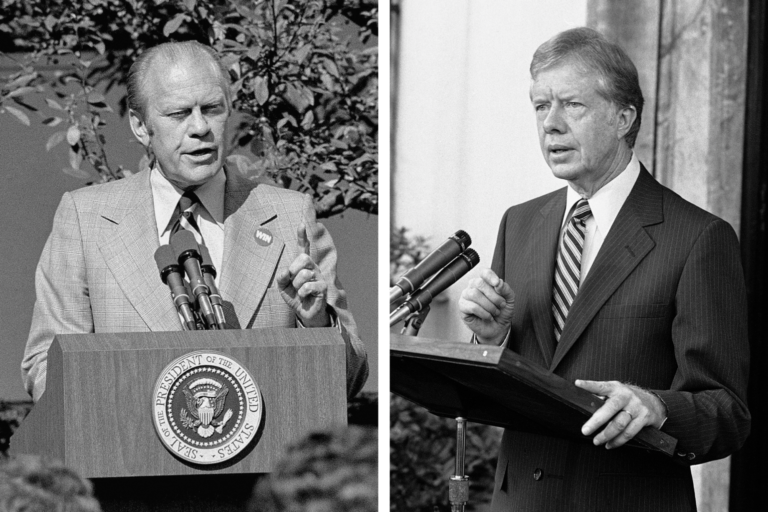

Those who remember the 1970s may also recall that stagflation arguably unraveled two presidencies — Gerald Ford’s and Jimmy Carter’s — and nearly destroyed another: Ronald Reagan’s. “Whipping” inflation, driving down interest rates and reversing job losses in a period of industrial decline became a central obsession of all three administrations, and as each president found, it was a game of whack-a-mole: Each solution seemed to deliver unintended consequences that only rendered the problem more vexing.

But Trump might be in an even more dire position. What made Ford, Carter and Reagan so similar was that stagflation was a problem that was visited upon them, owing largely to exogenous or structural developments they had scant ability to control. Trump’s looming stagflation crisis, on the other hand, is one of his own making. The public was hard enough on past presidents who failed to fix the problem. Time will tell how just harshly voters will appraise Trump for potentially creating it.

Through aggressive tariffs and extreme cuts to the government workforce — as well as health, science and social service funding — Trump’s policies threaten to directly increase production costs and consumer prices, fueling inflation and almost guaranteeing that the Federal Reserve Board will keep interest rates high. Additionally, the resulting economic uncertainty discourages business investments and disrupts supply chains, which can stifle economic growth, setting the stage for higher unemployment.

Why would anyone elect to do this? Trump maintains that, contrary to what most economists believe, it will reinvigorate American industry in his nationalist vision. But those around the president would do well to brush up on their 1970s history. It isn’t pretty. But it is incredibly revealing about both the economic and the political situation that seems to be rising from the grave — with a hand from the president of the United States.

The post-World War II period in the United States was marked by a prolonged stretch of economic prosperity, characterized by robust growth, and low inflation and interest rates. The economy experienced unprecedented expansion, driven by high levels of consumer spending, technological innovation and government investment in infrastructure. This growth notwithstanding, inflation remained relatively stable throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, averaging around 1 to 3 percent annually, while interest rates also stayed low, fostering widespread home ownership and the rise of a burgeoning middle class.

It was good while it lasted. But nothing lasts forever.

The era of economic stability came to an abrupt crash in the late 1960s and early 1970s, as a combination of federal spending, global supply shocks and misguided policy decisions led to a decade of high inflation and soaring interest rates.

Grain pours into a truck on farmland. Grain pours into a truck during a wheat harvest in Kansas in 1974. President Richard Nixon’s decision to extend credit to the Soviets for purchasing U.S. grain contributed to the depletion of domestic grain reserves and led to soaring food prices. | AP

The origins of high inflation and interest rates trace in part to a sharp increase in federal spending due to the Vietnam War. Between 1965 and 1968, federal spending surged by 60 percent. This spike led to “cost-push” inflation, wherein increased government expenditures overheated the economy, generating low unemployment and a tight labor market, and thereby pushing wages and, subsequently, prices upward. Although the Johnson administration attempted to counteract this effect with a temporary 10 percent tax increase to reduce aggregate demand, the measure failed to have the desired impact.

Further driving inflation was a series of supply shocks in the 1970s, particularly in the food and energy sectors. A confluence of events, including poor harvests in eastern Europe — and President Richard Nixon’s subsequent decision to extend credit to the Soviets for purchasing U.S. grain — depleted domestic grain reserves and led to soaring food prices. In 1973 alone, food costs rose by an astounding 30 percent, and the price of meat jumped by 75 percent within three months. Concurrently, America’s support of Israel during the Yom Kippur War prompted OPEC to impose an oil embargo, which led to a quadrupling of oil prices and widespread fuel shortages.

Nixon’s economic policies also played a role. His push to maintain a full-employment budget — in other words, he didn’t put his foot on the brake — coupled with the Federal Reserve’s expansionist monetary policy, further overheated the economy.

All of this would have been bad enough had America’s once robust industrial base not experienced a crippling reversal. Until the early 1970s, most experts assumed that inflation and unemployment enjoyed an inverse relationship. But that logic got turned on its head.

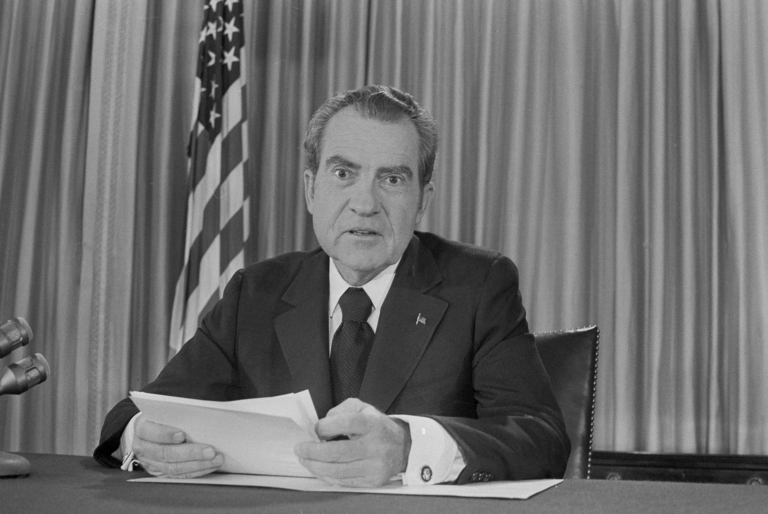

President Richard Nixon sits at a desk.

President Richard Nixon after delivering a televised address in June 1973, where he told the nation he had ordered an immediate freeze on all retail prices for up to 60 days. | Charles Tasnadi/AP

For the better part of 25 years, American industry and manufacturing had created good-paying union jobs with strong benefits like defined-benefit pensions and private healthcare. But by the early ’70s, those jobs began disappearing due to a combination of outdated technology, increased foreign competition and corporate missteps. The signs of ruin were everywhere. In Detroit, the Chrysler Corporation announced it was on the verge of bankruptcy. In Youngstown, Ohio, the city government was forced to close the broken-down bridges that spanned the Mahoning River, as there was no money left to repair them. In Aurora, Minnesota, once a prosperous mining town in the state’s famed Iron Range, forlorn residents looking to pick up stakes and start over in a different part of the country tried selling their homes at a loss, only to find that there were no buyers to be found.

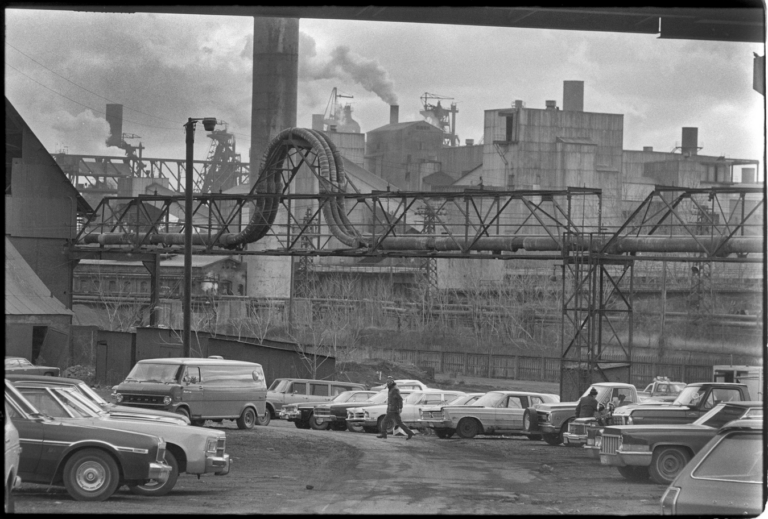

The example of American steel manufacturing is telling. American steel firms, such as those in Youngstown, had once been an engine of national economic power. But they had been slow to invest and modernize, and foreign competitors adopted new technologies that made their steel production faster and more efficient. Compounding the problem, federal policy inadvertently strengthened foreign steel production. Following World War II, American assistance helped rebuild efficient steel facilities in Europe and Japan while allowing these countries to impose high tariffs on U.S. steel. At the same time, American companies invested in modern plants abroad rather than upgrading their domestic operations, resulting in increased import penetration in the U.S. market. Furthermore, conglomerate ownership of steel companies like Youngstown Sheet & Tube led to profits being siphoned off to finance non-steel ventures, further weakening the industry’s competitive position. The result was a wave of plant closures and job losses, as seen in once-prosperous Youngstown, where over 50,000 steel jobs vanished within half a decade.

All of this led to the anomaly known as stagflation. By the time Ford assumed office, U.S. Gross National Product was dropping at an annual rate of 4.2 percent. Price inflation rose to 16.8 percent, unemployment rates soared as high as 8.9 percent, and — because the Fed eventually had to raise interest rates in an attempt to quell rising price inflation — mortgage rates hovered at a prohibitively high level of about 10 percent. Ford’s exasperation was on display when he told a meeting of the American Business Council in December 1974: “We are in a recession. Production is declining, and unemployment, unfortunately, is rising. We are also faced with continued high rates of inflation greater than can be tolerated over an extended period of time.”

Truck drivers turn their thumbs down as a truck passes a Shell Oil refinery. Truck drivers turn their thumbs down in protest of rising fuel prices as a truck passes the Shell Oil refinery in Sewaren, New Jersey, in February 1974. | AP

Workers get into their cars in a parking lot, with a steel plant looming in the background.

Workers leave Youngstown’s Jones & Laughlin Brier Hill Works, formerly Youngstown Sheet and Tube, for the last time in December 1979. | Ernie Mastroianni/Alamy

Matters didn’t improve over the course of the decade. By the first quarter of 1980, inflation was growing at an annualized rate of over 18 percent and economic growth slowed to a sluggish 1.2 percent. Unemployment hovered around 7.5 percent. Mortgage rates had already climbed as high as 20 percent, which meant that a $100,000 home loan that once carried monthly payments of $421 now cost the average family $1,425 per month — equivalent to nearly $6,000 in today’s terms.

Numbers alone don’t tell the full story. Supply shocks generated unusual side effects, like gas shortages. Taking advantage of political disruptions in Iran, in 1979 OPEC doubled oil prices, setting off a massive inflationary spiral in the United States. By mid-year, over half the gas stations in America were forced to shut down for want of supplies. As journalist Nicholas Lemann remembered, “the automotive equivalent of the Depression’s bank runs began. Everybody considered the possibilities of not being able to get gas, panicked, and went off to fill the tank; the result was hours-long lines at gas stations all over the country.” Driving on the Central Expressway in Dallas, Lemann ran out of gas and stalled by the side of the road. “The people driving by looked at me without surprise,” he noted, “no doubt thinking, ‘Poor bastard, it could have happened to me just as easily.’”

For those who were fortunate enough to be employed, stagflation also introduced a concept called “bracket creep.” As wages increased to keep pace with rising prices, many working Americans found themselves suddenly thrust into higher tax brackets. The resultant tax hike often exceeded the increase in wages, which meant that in real dollars the average blue-collar worker — if they were lucky enough to keep their job — experienced a sharp reduction in take-home pay, even as fuel, food and clothing prices soared.

Successive presidents grappled with the challenges of stagflation. Each found that their prescriptions failed to address the underlying problem but often created political pain in the process.

Nixon initially reversed course and tried to quell inflation by maintaining a balanced budget and urging the Federal Reserve to limit money growth, but his failure to recognize the impact of supply shocks — like the 1973 oil crisis — and inattention to structural causes of de-industrialization rendered that approach ineffective, as America experienced still higher unemployment and prices.

Ford initially pursued austerity measures, including tax hikes and budget cuts, but faced backlash when the economy continued to worsen. His “Whip Inflation Now” campaign, which encouraged personal sacrifice to curb inflation, earned wide ridicule. Eventually, Ford reversed course under pressure from Congress, shifting to tax cuts, which neither tempered inflation nor stimulated the economy.

Carter focused on reducing the budget deficit while simultaneously attempting to manage rising energy costs. His efforts to cut social spending and impose stricter fiscal controls clashed with calls for increased government intervention. He also introduced an ambitious energy policy aimed at reducing consumption and promoting conservation, but Congress significantly weakened it due to popular opposition. Despite his intentions, the resulting legislation ended up reducing capital gains taxes rather than increasing them, inadvertently worsening the deficit. Carter also failed to address the deeper structural issues, such the transition from manufacturing to a service economy.

Left: President Gerald Ford, wearing a Whip Inflation Now button, holds a news conference at the White House in October 1974, after announcing his anti-inflation program. Right: President Jimmy Carter delivers a statement criticizing a decision by OPEC countries to raise the price of oil, in Tokyo, Japan, in June 1979. | AP

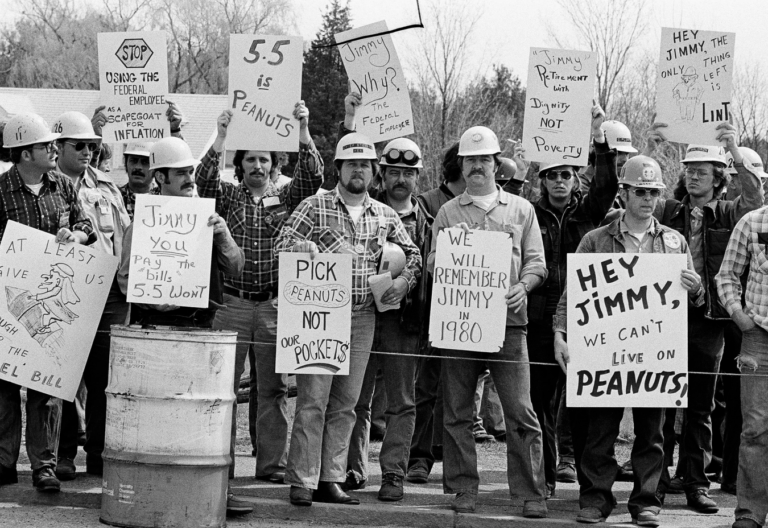

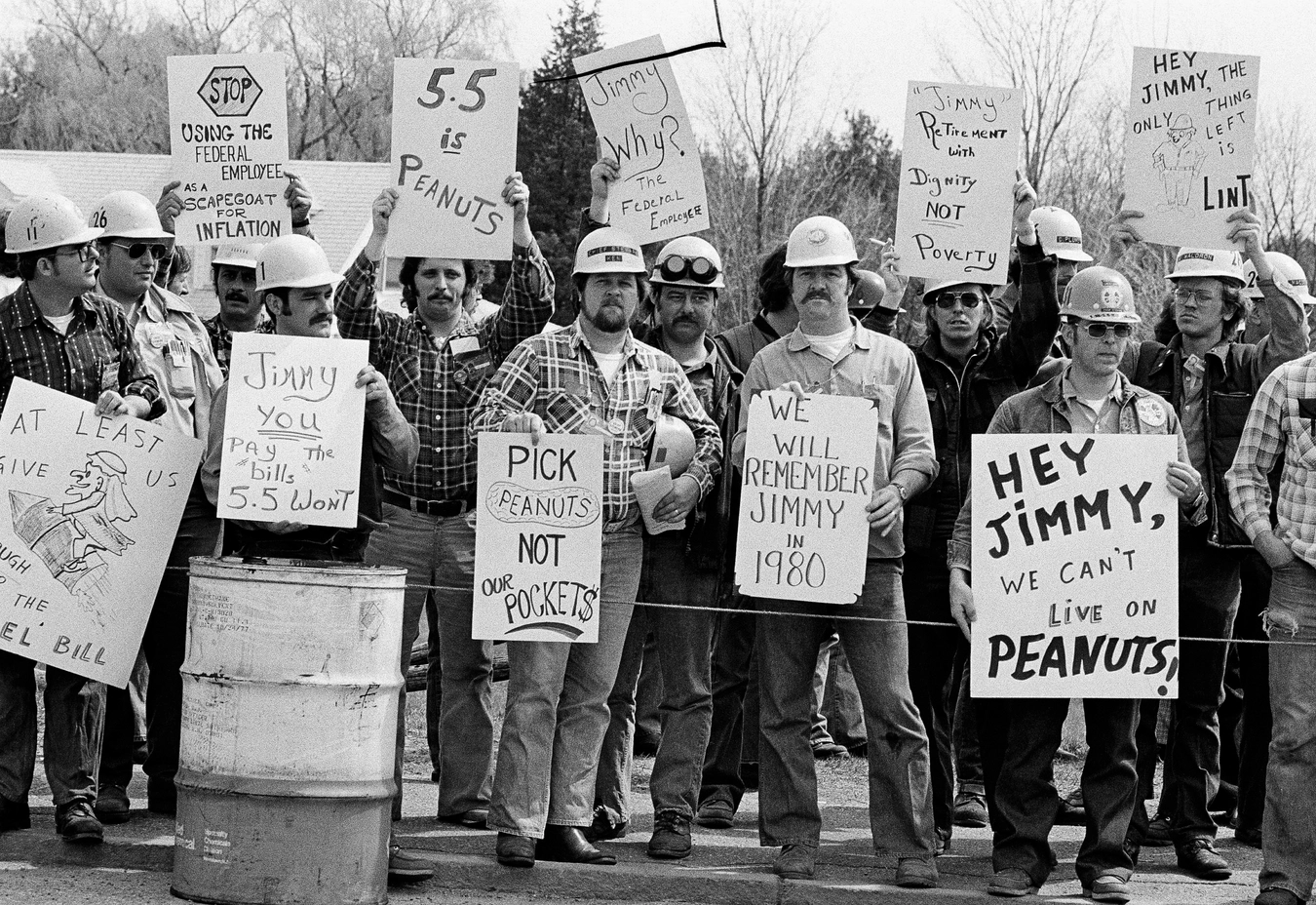

A group of metal trade workers protests against Jimmy Carter’s wage ceiling.

Both presidents suffered chronically low poll numbers, largely because of the state of the economy. Ford bottomed out at 36 percent in March 1975, while Carter’s approval rating plummeted to 28 percent in July 1979, in perfect sync with the upward movement of the inflation and unemployment rates.

During the early years of Reagan’s presidency, the Federal Reserve, under Chairman Paul Volcker, finally took aggressive action to combat the high inflation that had plagued the economy throughout the 1970s. Volcker implemented a tight monetary policy, drastically raising interest rates to nearly 20 percent by 1981. While this strategy eventually succeeded in bringing inflation under control, it caused severe economic pain in the short term, triggering the deepest recession since the Great Depression. Unemployment soared to over 10 percent, and businesses struggled with high borrowing costs, leading to widespread bankruptcies and public discontent. The economic downturn was so severe that Reagan’s approval ratings plummeted, and by the 1982 midterm elections, his party suffered heavy losses in Congress. Many political observers speculated that the lingering economic malaise might cost Reagan a second term. Of course, the subsequent economic recovery, fueled by lower inflation and tax cuts, ultimately bolstered Reagan’s reelection prospects in 1984.

Each of these presidents — Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan — struggled to address the scourge of stagflation. Ford and Carter lost their re-election bids, in no small part because they couldn’t contain it.

And yet Trump seems to be inviting it.

President Donald Trump holds up a report on foreign trade barriers as he delivers remarks in the Rose Garden.

Trump speaks during an event where he announced new tariffs in the Rose Garden at the White House, on April 2, 2025. | Francis Chung/POLITICO

His economic policies, particularly the aggressive and indiscriminate implementation of across-the-board tariffs that will affect even our most important trading partners — like China, Canada, Mexico and the European Union — are expected to increase the cost of imported goods, leading to sharply higher consumer prices. Simultaneously, retaliatory measures from affected countries will almost certainly suppress U.S. exports, negatively impacting domestic manufacturing and leading to job losses. The administration’s stringent immigration policies may further exacerbate labor shortages in critical sectors like agriculture, food processing and construction, adding upward pressure on wages and production costs, which can also fuel inflation. All of these policies could interrupt supply chains and production and lead to shortages of critical materials.

Perhaps Trump truly believes that the tariff-happy 1890s were a golden age for the American economy — though historians will tell you this wasn’t so. Whatever the motivation, stagflation may be back sooner than we think. And if the 1970s are any indication, they won’t just be a hardship for the American people — they’ll also be a self-inflicted political wound for Trump and his party.

Buyer beware.

Excepts: Politico

Joshua Zeitz, a Politico Magazine contributing writer, is the author of Lincoln’s God: How Faith Transformed a President and a Nation (May 2023). Follow him @joshuamzeitz.

COMMENTS