The decline of the media is sapping journalism of a crucial tool.

A general view of the Kansas City bureau of the Associated Press. In the foreground is the East desk. Next is the Coast desk, then the State desks and in the background the Local desk, on April 22, 1940. | AP Corporate Archives

Wounded and limping, doubting its own future, American journalism seems to be losing a quality that carried it through a century and a half of trials: its swagger.

Swagger is the conformity-killing practice of journalism, often done in defiance of authority and custom, to tell a true story in its completeness, no matter whom it might offend. It causes some people to subscribe and others to cancel their subscriptions, and gives journalists the necessary courage and direction to do their best work. Swagger was once journalism’s calling card, but in recent decades it’s been sidelined. In some venues, reporters now do their work with all the passion of an accountant, and it shows in their guarded, couched and equivocating copy. Instead of relishing controversy, today’s newsrooms shy away from publishing true stories that someone might claim cause “harm” — that modern term that covers all emotional distress — or even worse, which could offend powerful interests.

Every aging generation of journalists must have complained, at one point or another, about swagger’s demise. But this time, the fall is demonstrable. A recent piece by Max Tani in Semafor attributed the new timidity to legal threats from subjects of news stories. “In 2024, it’s harder than ever to get a tough story out in the United States of America,” Tani writes, citing the risk of lawsuits and increased insurance premiums. The new equation “has given public figures growing leverage over the journalists who now increasingly carry their water.” Tani cited several examples of publications backing down, including Esquire and the Hollywood Reporter backing off from a critical story about podcaster Jay Shetty, the surrender by Reuters and other outlets to India’s legal demands about an exposé, and the unpublishing of a biting Formula 1 story in Hearst’s Road & Track.

Perhaps the clearest marker of swagger going AWOL is the fact that nobody has risen to replace the late Christopher Hitchens on the lecture circuit, on cable news, in books and in the pages of our best publications. If he were resurrected today, who would hire him? And if they did, how long would it take for the staff to petition the bosses to fire him?

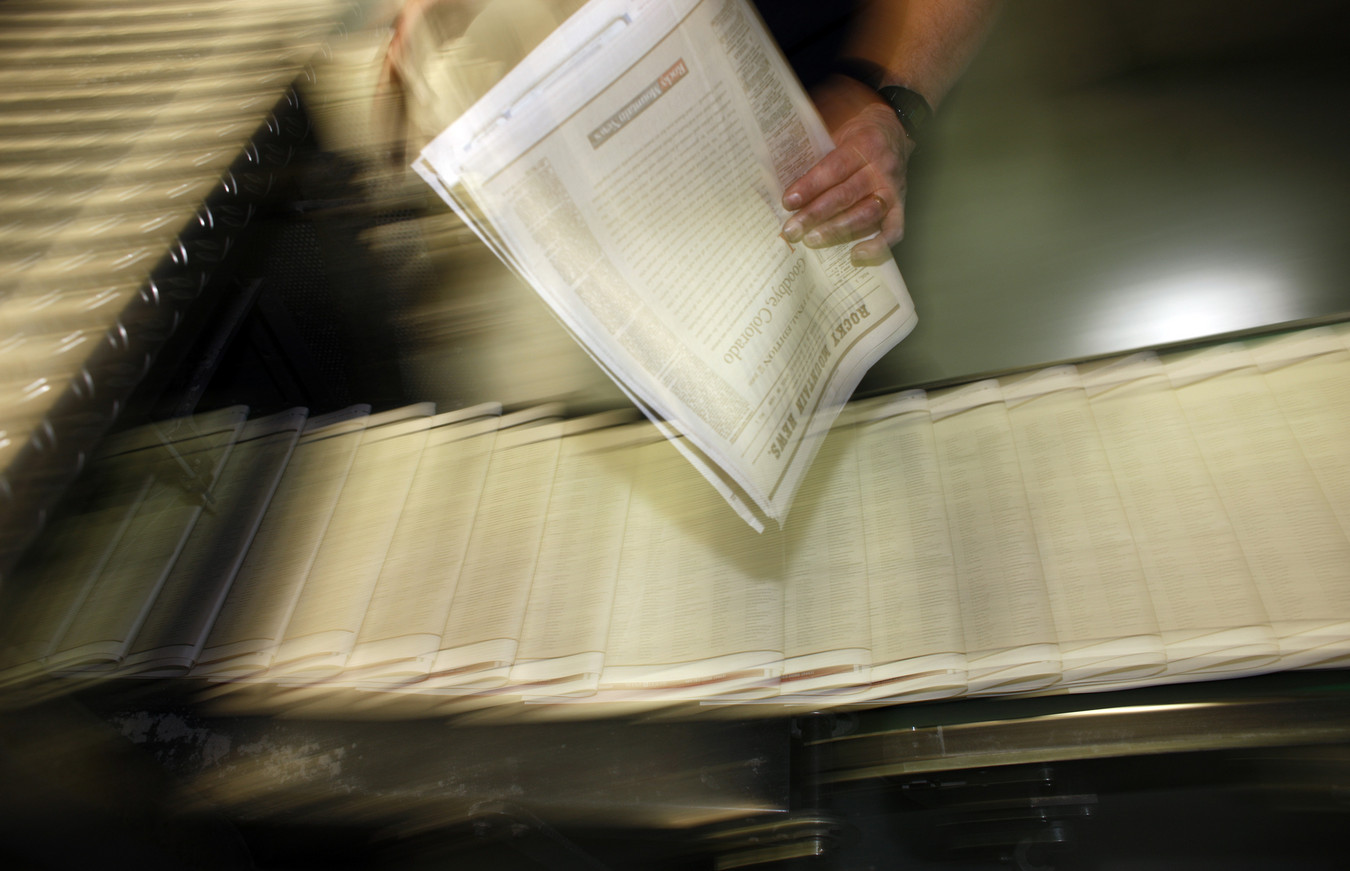

The loss of journalistic swagger can be measured partly in numbers. A generation ago, the profession summoned cultural power from employing almost a half-million people in the newspaper business alone. Now, more than two-thirds of newspaper journalist jobs have vanished since 2005, and it is widely accepted that the trend will continue in the coming decades as additional newspapers and magazines falter and slip into the publications graveyard.

But the loss is about more than just head count. The psychological approach journalists bring to their jobs has shifted. At one time, big city newspaper editors typified by the Washington Post’s Ben Bradlee strode their properties like colossuses, barking orders and winning deference from all corners. Today’s newspaper editor comes clothed in the drab and accommodating aura of a bureaucrat, often indistinguishable from the publishers for whom they work. These top editors, who once ruled their staffs with tyrannical confidence, now flinch and cringe at the prospect of newsroom uprisings like the ones we’ve seen at NBC News, the New York Times, CNN and elsewhere. You could call these uprisings markers of swagger, but you’d be wrong. True swagger is found in works of journalism, not protests over hirings or the publication of a controversial piece.

Treading softly so as not to rile anybody, these editors impose that style on their journalists, many of whom do their work in a defensive crouch instead of the traditional offensive stance. Often throttled by their top editors, today’s journalists also find themselves fighting a second front against politicians who now direct their campaigns at reporters as much as they do their opponents. The public appears to hate them too, according to polls that claim they’re not trustworthy. Inside the newsroom, they face standards editors who have steadily expanded their stylebook of banned words in a crusade to reduce to zero the chances that readers might take umbrage at news copy.

Thanks to technological trends, cultural shifts, business and advertising changes, and legal rumblings, journalism and journalists have lost the centrality in America that was theirs for almost a century and a half. The press has become no weakling. Obviously, good work is still done but with blunted rather than sharpened teeth compared with previous decades. Nor will the craft vaporize upon some near future event horizon. But like its other sister institutions of influence — Hollywood, religion, the novel, the courts, public schools, et al. — it no longer strides with its former confidence. Ask any journalist about their depleted esprit de corps and you will hear a litany of lamentations.

THE MEDIA ISSUE

Swagger should not be mistaken for shouting and galumphing in the newsroom or for its cousin, gonzo journalism, invented by Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas author Hunter S. Thompson and imitated by so many lesser writers for the last five decades. Nor is it partisan.

Swagger, which made journalism a delight to practice and a joy to read, came in many forms, from the sting of Mary McGrory’s dispatches from Capitol Hill to the antics of editor Jim Bellows at the Washington Star to the brash pieces filed by Michael Kelly from D.C. to Iraq and Nora Ephron’s biting commentaries on contemporary life. And it still speaks its name if you know where to look for it, such as the feature stories of Olivia Nuzzi and Kerry Howley at New York magazine and the work of CNN’s Clarissa Ward from war zones. Former Washington Post reporter Wesley Lowery practically embodies swagger.

The loss of swagger has left readers struggling to decipher pieces that appear to have been reported through a veil, or worse still, sound as if they were manufactured by the public affairs department of a cabinet-level agency.

What routed swagger, and can we get it back?

The Business Erodes

Former Washington Post Style editor Ned Martel recalls that when Kevin Merida became the paper’s national editor in 2008, he placed a handwritten sign by his office spelling out the word “Swagger.”

Merida, who recently resigned as the executive editor of the Los Angeles Times, confirms the story: “If somebody reliable said I did, I probably did.”

“It’s harder to be confident, and exude that confidence in newsrooms — given the state of our industry. But leaders should find their inner swagger,” Merida says. “I don’t like to generalize, as every newsroom is different. But cautiousness, lack of ambition, being too quick to abandon experiments or being afraid to try them, all are signifiers. To quote the immortal, A Tribe Called Quest: ‘Scared money don’t make none.’”

Steve Chapman, who has worked as a Chicago Tribune columnist and editorial writer for four decades, attributes the decline of swagger, in part, to the general winding down of the business.

“Talented, temperamental egomaniacs didn’t have to worry about pissing off their bosses because they could walk across the street to a competing paper. Chicago had four dailies in the ’70s,” he says.

Journalism, he adds, has become a profession for college-educated, intellectual types while nudging aside the working-class kids who used to break into the business as copy boys or stringers. “We don’t see the big, colorful, spit-in-your-eye columnists who once roamed the newsroom — Mike Royko, Jimmy Breslin, Jack Germond, Pete Hamill and Nicholas von Hoffman.”

Instead of editors and reporters settling their differences in pitched battles, today’s journalists sit down for mannered Zoom sessions. “Forty or 50 years ago, one ill-considered column wouldn’t be a disaster,” Chapman says. “Today, it can be. Ask James Bennet.” Bennet, you recall, was unfairly run out of the New York Times for publishing the words of a U.S. senator. Being forced to write and edit, forever looking over your shoulder, “encourages conformity and caution, the antithesis of swagger,” Chapman warns.

Another significant well-spring of talent and model of swagger, the alternative weekly, has been all but vanquished. The late David Carr edited Twin Cities Reader and Washington City Paper before making his national mark at the New York Times. Alt-weekly writers such as Ta-Nehisi Coates, Katherine Boo, Liza Mundy, Jonathan Gold, Matt Taibbi, Susan Orlean, Jim DeFede and too many others to mention never treaded softly as they moved into the greater mainstream. The near-evaporation of the alt-weekly is a national tragedy. Where every one of the top 100 markets once hosted a successful alt-weekly that served as a swagger example and a talent pool for the dailies, you now have a struggling handful of them.

In the pre-Internet, pre-cable time, journalistic outlets like Time, Newsweek, Look and the Saturday Evening Post dominated the mass media. The Washington Post spoke to everybody from the president to the post office clerk and could boast that 65 percent of metropolitan area households subscribed. Everyone listened. Now, the press’ status as a pacesetter and respected authority has evaporated, and journalists know it.

As readers look away, it’s led to the primary cause of journalism’s decline: lack of advertising. It’s a mistake to talk about the “journalism business” when the primary function of newspapers and magazines was, for so long, to convey the message of mass advertising. As advertisers learned Internet advertising was much more effective and often cheaper than print, they defected to places like Google and Facebook that didn’t need news to attract those eyes. Where advertising once accounted for 80 percent of revenue at most newspapers in their heyday, circulation revenue and ad revenue are equal across the industry. At places like the New York Times, 60-plus percent of revenue comes from readers. Declining circulation logically followed declining advertising at newspapers, with a third of all of them folding since 2005. A generation ago, healthy revenues gave publications the resources to fight legal battles. That’s less true today.

Cultural Cachet Wanes

Newspaper culture lost its conviction as it became aware of its own dimunition. Yesterday’s journalists thought the world revolved around what their newspaper wrote. Today’s journalists resign themselves to the fact that their copy simply doesn’t matter as much.

“We no longer have a culturally cohesive country,” says Glenn Frankel, who knows journalism from the inside, having worked for decades at the Washington Post, and from the ivory tower after a stint as the director of the School of Journalism at the University of Texas at Austin.

This loss of audience to social media, sports and entertainment has diminished journalists’ sway, as Matthew Powers and Sandra Vera-Zambrano write in their recent book, The Journalist’s Predicament: Difficult Choices in a Declining Profession. Journalists don’t need to consult the latest round of layoffs at their outlets to understand they’ve lost prestige in the culture, or to see that acquaintances with similar educations out-earn them.

“Journalism’s imperiled economic basis reduces the total number of jobs available and creates less-than-ideal work conditions,” Powers and Vera-Zambrano write. It’s not uncommon for a barrage of layoffs to be followed by demands by bosses that reporters and editors do more with less. Meanwhile, new information ecosystems “have loosened journalism’s monopoly on the production and distribution of legitimate information and erode[d] the sense of importance that stemmed from that exclusivity.”

Nobody ever became a journalist in order to become popular. The broad-stroke portrayals in movies and novels taught us, accurately enough, that journalists tend toward the coarse, vulgar, impudent and nosy. For many years, journalists were generally admired for those attributes in the way that the beef butcher is admired for the scars on his hands.

But thanks, in part, to a fall in status, as well as ever-irrational attacks from politicians like Donald Trump, today’s journalists routinely experience ridicule and harassment at public events like rallies and demonstrations. They’re not precisely pariahs in the new environment, but they’re no longer considered heroes in many places. Journalists don’t deserve any special pity, it should be noted. Police officers, teachers and even doctors often suffer more from the slings and arrows of the mob. But for journalists, the fall has been spectacular and seems never-ending.

Hanging over journalism like a gibbous moon is Terry “Hulk Hogan” Bollea’s successful lawsuit against Gawker, financed by the billionaire Peter Thiel, which Tani notes in his Semafor piece. Thiel’s successful action, which forced the site to shutter in 2016, has journalists everywhere looking over their shoulders in worry. In the new climate, law firms have built practices devoted to blocking the publication of tough-minded stories with formal legal warnings.

Perfectly fine publications do exist, and they deserve our support. For instance, there’s the Atlantic, which couldn’t win more National Magazine Awards if the contest were fixed. With stalwart writers like Caitlin Flanagan and Mark Leibovich, the magazine shows it can go full bravado when it wants to. But what’s its excuse for not breaking more icons? Too often, our media seems like it was produced to be consumed by our parents, most of whom are dead.

Reason magazine’s Nick Gillespie blames the decline of swagger, in part, to generational forces.

“Millennials and Gen Z have been bred like human veal by their Boomer and Gen X parents who made sure their kids were constantly being surveilled and optimized for success in SATs, sports and entry into the Establishment pipeline,” he says. “Can we be surprised that such a system has produced generations of journalists who endlessly describe anything they disagree with as misinformation and want to control and regulate everything like the room temperature in an after-school enrichment program?”

This attitude has permeated the press, as editors recoil from publishing anything that might cause anyone offense.

The Pipeline Runs Dry

For the next generation, the future is dismal. And the youth know it. With an eye on the shrinking industry, fewer and fewer students now collect bachelor’s degrees in journalism, according to numbers collected by MIT Media Lab’s DataUSA site. Sensing the trend, schools like the University of New Hampshire, Ohio Wesleyan, Arkansas State University and others have ended their journalism programs in the last academic year or cut way back.

Journalists, like those in other professions, sharpen their teeth on the chew toy of experience. Reporters still begin their careers as student journalists or freelancing or interning at a publication between semesters in school before landing at their first publication.

In the process, they learn when to duck and when to throw the punch. They confer with libel attorneys and figure out how to publish true stories without getting sued. They climb the ladder at small and regional publications, and some of them reach the big leagues of the major outlets, accumulating the swagger you need to challenge presidents, CEOs, billionaires and other notables.

“I remember one editor looking at me when I broke my first story on the Wedtech scandal and sneering, ‘You’re wading in tall grass on this one.’ Didn’t faze me. I would just press ahead,” says investigative ace Marilyn Thompson, who is now at ProPublica.

“Some people saw this as ‘swagger’ and regarded me as an asshole with a sweet Southern accent, who dared come to New York or Washington to look under moldy rocks,” she says. “I think swagger survives, though it is harder to execute with layers of editing and lawyering and endless rewriting. I worked with the Clarence Thomas team last year, and those young guys have the right stuff.”

But with the feeder institutions that produce journalists — J-schools and small publications — atrophying, there’s a real risk that newsroom culture shifts to a more tempered mindset, taking swagger with it. Granted, launching pads for young journalists still exist, such as Robert Allbritton’s NOTUS, POLITICO’s Fellows program and the New York Times’ Newsroom Fellowship Program, among others, but these aren’t enough. They offer scores of opening slots compared to the thousands of entry-level jobs that once existed across the country where young journalists could study walking and eventually advance to swaggering.

As journalism opportunities continue to decline, will the sharpest, most contentious minds that make the best journalists still be attracted to the business? Absent the status rewards its workers collected, who will want the job that was so appealing to earlier generations? “As I look back over a misspent life I find myself more and more convinced that I had more fun doing news reporting than in any other enterprise,” journalist H.L. Mencken wrote in 1946. “It is really the life of kings.”

Regaining Some Swagger

What then should we do? Enroll journalism students and novice journalists in academies of self-esteem? Obviously not. Find a stash of Ben Bradlee’s hair and clone a hundred of him? Please, no. Spike the office coffee with stimulants? Nobody wants a return to the locker room ethos of earlier newsrooms where a mist of testosterone hung in the air, where every other desk had an opened bottle of scotch on it, and where women and Black people, Latinos and Asian Americans were excluded from the enterprise. Surely there is a path back from the milquetoastery of contemporary journalism to something approximating swagger.

Like all 12-step programs, the first step is to understand that something is going wrong, something this piece has attempted to do. Can more be done?

Matt Labash, who earned his name as a swashbuckler at the Weekly Standard and now does business at the “Slack Tide” Substack newsletter, is one of many who cite the newsletter boom as a temporary fix, if not a solution. Leading Substackers Matt Taibbi, Bari Weiss and Nellie Bowles, and Matt Yglesias have profitably fled their mainstream jobs at Rolling Stone, the New York Times and Vox for Substack where they can get their swag on as much as they want to without having to deal with layers of management. They’ve also freed themselves from the sniping groupthink prevalent at so many newsrooms that identifies swagger as a crime of expression and seeks to extinguish it.

In the case of Weiss and Bowles’ Free Press, they’ve evolved from a modest blog to a 25-person newsroom in three years and added events and podcasts to the editorial mix. Most recently, they published NPR editor Uri Berliner’s swaggering inside critique of his employer and colleagues, which ripped the broadcaster for prioritizing process over substance.

Labash, who has attended church with Marion Barry and gone flyfishing with Dick Cheney, calls Substack a place where writers can be themselves without apology, and bring an audience along with their personality quirks.

“Humans respond most strongly to specificity,” Labash says. “To things they can relate to as fellow human beings. But if you make your writers sound like some bland AI generator, and AI can do their job, eventually, AI will. Which might very well be what a lot of publishers want, anyway.”

While not the immediate remedy to swagger’s decline, Substacks point to an entrepreneurial future where readers respond to spirited media. Elsewhere on the media horizon, we catch the sniff of swagger at outlets like Punchbowl News, the Ankler, Tablet, the Ringer, County Highway and 404 Media, to name a few, where challenging readers instead of coddling them comes first. If Substack has proved there’s an ample supply of readers willing to be challenged by bracing copy, perhaps editors will be willing to unleash the storehouses of repressed swagger in their newsrooms to feed the need. On the other hand, it could be that the fall of citadels of swagger like Buzzfeed News, the relaunched Gawker and Vice portend doom for swagger’s future.

Sometimes the emergence of a single new publication can alter the journalistic current. Spy magazine, founded in 1986 by Kurt Andersen and Graydon Carter, struck the journalism world like the Chicxulub asteroid. Spy brought equal measures of swagger, moxie, attitude, gumption and pinpoint reporting to magazine and newspaper journalism. Louis Rossetto’s Wired magazine, launched in 1993, did some of the same. Perhaps swagger’s resurrection will come in the form of a new publication or website that tosses off the zip-ties for freer expression.

Chapman, for one, doubts that the industry’s swagger will return any time soon.

“Journalism is so fragmented, and readers, viewers and profits so much harder to come by, that journalists have to be more careful with their audiences,” he says. “In some ways, journalism is better than it used to be, with higher standards of writing, ethics, accountability and analysis. Journalists are generally more respectful of and sensitive to groups that once got ignored or disparaged. I don’t want to go back to the old days. But we have lost some qualities that made journalism entertaining.”

If journalism is to regain the kingdom, it will need to call on top editors to lead the restoration with brass and daring. The same goes for the owners who shriek at the possibility of lawsuits. As former Vanity Fair and New Yorker editor Tina Brown put it to Tani, “Very few owners have balls anymore.” That’s true, but journalistic history show us they can be grown.

Like fighter pilots, journalists must be well-trained and confident but without being cowboys. Meekness produces journalism as gray as dishwater and no more tasty. If journalism is ever to regain its former — and rightful — status, it must first regain its swagger.

******

Jack Shafer is Politico’s senior media writer. He has written commentary about the media industry and politics for decades and was previously a columnist for Reuters and Slate.

Excerpts: Politico

COMMENTS