China is currently the world’s largest economy measured by purchasing power parity. As the rapid expansion of the Chinese economy reshapes the global geopolitical map, Western mainstream media has begun to define China as a new imperialist power that exploits cheap energy and raw materials from developing countries. Some Marxist intellectuals and political groups, drawing from the Leninist theory of imperialism, argue that the rise of monopoly Chinese capital and its rapid expansion in the world market have turned China into a capitalist imperialistic country.

Whether China has become an imperialist country is a question of crucial importance for the global class struggle. I argue that although China has developed an exploitative relationship with South Asia, Africa, and other raw material exporters, on the whole, China continues to transfer a greater amount of surplus value to the core countries in the capitalist world system than it receives from the periphery. China is thus best described as a semi-peripheral country in the capitalist world system.

The real question is not whether China has become imperialistic, but whether China will advance into the core of the capitalist world system in the foreseeable future. Because of the structural barriers of the capitalist world system, it is unlikely that China will become a member of the core. However, if China does manage to become a core country, the extraction of labor and energy resources required will impose an unbearable burden on the rest of the world. It is doubtful that such a development can be made compatible with either the stability of the existing world system or the stability of the global ecological system.

Is China a New Imperialist Country?

As China becomes the world’s largest economy (measured by purchasing power parity) and the largest industrial producer, China’s demand for various energy and raw material commodities has surged. In 2016–17, China consumed 59 percent of the world total supply of cement, 47 percent of aluminum, 56 percent of nickel, 50 percent of coal, 50 percent of copper, 50 percent of steel, 27 percent of gold, 14 percent of oil, 31 percent of rice, 47 percent of pork, 23 percent of corn, and 33 percent of cotton.1

A large portion of China’s demand for commodities is supplied by developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. In this context, Western mainstream media has described China as a new imperialist country exploiting developing countries. In June 2013, the New Yorker carried an article criticizing Chinese capitalists in Zambia for exploiting local copper resources and violating labor rights.2

In March 2018, the Week published an opinion article arguing that as China’s overseas investment skyrocketed, Africa had become a key destination of Chinese investment resulting in vicious exploitation of local resources and ecological disasters. The author further argued that, because of the authoritarian nature of the Chinese political system, Chinese imperialism would prove to be considerably worse than Western imperialism.3

The New York Times asked whether China had become a new colonial power. The writer indicated that China had used its One Belt, One Road Initiative to support corrupt dictators, induce recipients of Chinese investment into debt traps, and promote cultural invasions.4

A Financial Times commentator contended that as China pursued the Belt and Road Initiative and promoted various economic projects, the investment logic would inevitably turn some developing countries (such as Pakistan) into China’s client states. China is therefore “at risk of…embarking on its own colonial adventure.”5

One of the recent articles in the National Interest argues that “China is the imperialist power” in much of Africa today. It contends that what China wants in Africa is not some form of socialism, but control over Africa’s resources, people, and development potential.6

For Marxist scholars and political groups, debates on imperialism have been either directly based on or inspired by V. I. Lenin’s concept of imperialism originally proposed in the early twentieth century. According to Lenin, by the late nineteenth century, the basic relations of production in the developed capitalist world had evolved from free competitive capitalism to monopoly capitalism. The massive accumulation of capital by monopoly capitalists in combination with a saturation of domestic markets led to surplus capital that could only be profitably invested in colonies and underdeveloped countries by taking advantage of their cheap land, labor, and raw materials. The competition for capital export destinations in turn led to territorial partitions of the world by the major imperialist powers.7

In chapter 7 of Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, Lenin defined the five “basic features” of imperialism:

(1) the concentration of production and capital developed to such a high stage that it created monopolies which play a decisive role in economic life; (2) the merging of banking capital with industrial capital, and the creation, on the basis of this “finance capital,” of a financial oligarchy; (3) the export of capital as distinguished from the export of commodities acquires exceptional importance; (4) the formation of international monopolist capitalist associations which share the world among themselves, and (5) the territorial division of the whole world among the biggest capitalist powers is completed.8

World political and economic conditions have changed dramatically since the publication of Lenin’s Imperialism. While some of the “basic features” of imperialism proposed by Lenin remain relevant, the “territorial division of the whole world among the biggest capitalist powers” can no longer be understood in its original sense due to the victory of national liberation movements and decolonization of Asia and Africa in the mid–twentieth century. Marxist theories of imperialism (or concepts of imperialism inspired by the Marxist tradition) that evolved after the mid–twentieth century typically defined imperialism as a relationship of economic exploitation leading to unequal distribution of wealth and power on a global scale.9

In the contemporary debate on “Chinese imperialism,” Marxist theorists who contend that China has become a “capitalist imperialist country” usually argue that China has become imperialist in the Leninist sense—that is, internally, China has become a monopoly capitalist country; externally, the monopoly Chinese capital has manifested itself through massive exports of capital. For example, N. B. Turner has argued that both state and private monopoly capital had been established in China and the four largest state-owned banks controlled the “commanding heights” of the Chinese economy, demonstrating the dominance of finance capital. Turner further noted that China had accumulated enormous overseas assets and become one of the largest capital exporters in the world, exploiting workers and raiding resources in various parts of the world.10

David Harvey, one of the world’s best-known Marxist intellectuals, has recently contended that China’s holding of large chunks of U.S. government debt and the Chinese capitalist land grabs in Africa and Latin America have made the issue of whether “China is the new imperialist power” worthy of serious consideration.11

There have also been lively debates on whether China has become imperialist among Chinese leftist activists within China. Interestingly, a leading advocate of the proposition that China has become imperialist is Fred Engst (Yang Heping), the son of Erwin Engst and Joan Hinton, two U.S. revolutionaries who participated in China’s Maoist socialist revolution. In “Imperialism, Ultra-Imperialism, and the Rise of China,” Yang Heping (using the pen name Hua Shi) argued that the Chinese state-owned capital group had become the world’s single largest combination of industrial and financial capital and the world’s most powerful monopoly capitalist group. According to Yang, China’s demand for resources has already led to intensified imperial rivalry with the United States in Africa and Southeast Asia.12

Imperialism and Superprofits

Lenin considered imperialism to be a stage of capitalist development based on monopoly capital. For Lenin, monopoly capital did not simply mean the formation of large capitalist groups but large capitalist enterprises that had sufficient monopoly power to make superprofits—profits far above the “normal” rates of return under free competitive conditions.

Using available business information at the time, Lenin cited several examples of superprofits of monopolist capitalist businesses. The Standard Oil Company paid dividends between 36 and 48 percent on its capital between 1900 and 1907. The American Sugar Trust paid a 70 percent dividend on its original investment. French banks were able to sell bonds at 150 percent of their face value. The average annual profits on German industrial stocks were between 36 to 68 percent between 1895 and 1900.13

After elaborating the five basic features of imperialism, Lenin immediately said that “we shall see later that imperialism can and must be defined differently if consideration is to be given, not only to the basic, purely economic concepts…but also the historical phase of this stage of capitalism in relation to capitalism in general.” In chapter 8 of Imperialism, Lenin further argued that export of capital was “one of the most essential bases of imperialism” because it allowed the imperialist countries to “live by exploiting the labour of several overseas countries and colonies.” The superprofits exploited from the colonies in turn could be used to buy off the “upper stratum” of the working class who would become the social base of opportunism in the working-class movement: “Imperialism means the partition of the world, and the exploitation of other countries besides China, which means high monopoly profits for a handful of very rich countries, creating the economic possibility of corrupting the upper strata of the proletariat.”14

In the preface to the French and German editions, Lenin further elaborated:

[It] is precisely the parasitism and decay of capitalism, which are the characteristic features of its highest historical stage of development, i.e., imperialism.… Capitalism has now singled out a handful (less than one-tenth of the inhabitants of the globe; less than one-fifth at a most “generous” and liberal calculation) of exceptionally rich and powerful states which plunder the whole world simply by “clipping coupons.”… Obviously, out of such superprofits (since they are obtained over and above the profits which capitalists squeeze out of the workers of their “own” country) it is possible to bribe the labour leaders and the upper stratum of the labour aristocracy.15

Lenin considered this to be a “world-historical phenomenon.”

Thus, for Lenin, capitalist imperialism is not simply associated with the formation of large capitals and export of capital. It inevitably leads to and has to be characterized by “high monopoly profits” or “superprofits” through the plunder of the whole world. It is also interesting to note that, for Lenin, imperialism as a “world-historical phenomenon” has to be based on the exploitation of the great majority of the world population by a “handful of exceptionally rich and powerful states,” which Lenin estimated to include a population between one-tenth and one-fifth of the world total. Thus, imperialism must be a system where a small minority of the world population exploits the great majority. It cannot possibly be a system in which the majority exploits the minority.

If we apply Lenin’s concept of imperialist superprofits to the Chinese context, what do we find? Has China already become an imperialist country that is plundering the whole world simply by “clipping coupons”?

Using conventional international balance of payment accounting, China has indeed become a large capital exporter and accumulated enormous overseas assets. But these “assets” need to be analyzed.

From 2004 to 2018, China’s total foreign assets increased from $929 billion to $7.32 trillion. During the same period, China’s total foreign liabilities (that is, total foreign investment in China) increased from $693 billion to $5.19 trillion.16 This means China had a net investment position of $2.13 trillion at the end of 2018. That is, China has not only accumulated trillions of dollars of overseas assets but also become a large net creditor in the global capital market. This seems to support the argument that China is now exporting massive amounts of capital and therefore qualifies as an imperialist country.

However, the structure of China’s overseas assets is very different from the structure of foreign assets in China. Out of China’s total overseas assets in 2018, 43 percent consists of reserve assets, 26 percent is direct investment abroad, 7 percent is portfolio investment abroad, and 24 percent is other investment (currency and deposits, loans, trade credits, and so on). By comparison, out of total foreign investment in China in 2018, 53 percent is foreign direct investment, 21 percent is foreign portfolio investment, and 26 percent is other investment.

Thus, while foreign investment in China is dominated by direct investment, an investment form consistent with the foreign capitalist attempt to exploit China’s cheap labor and natural resources, reserve assets account for the largest component of China’s overseas assets.

China’s reserve assets reflect largely the accumulation of China’s historical trade surpluses and are mostly invested on low-return but “liquid” instruments such as U.S. government bonds. These assets theoretically represent China’s claims on future supplies of goods and services from the United States and other developed capitalist countries. But these claims may never be realized because the United States and other developed capitalist countries simply do not have the production capacity to produce within a reasonable period of time the extra goods and services that may correspond to the more than three trillion dollars of foreign exchange reserves held by China. If China uses a large portion of its reserves to buy raw material commodities or exchange the reserves into other assets, it would dramatically drive up the prices of these commodities or other assets and China would suffer a massive capital loss (a large reduction of the purchasing power of China’s reserves). In addition, China needs to hold several trillion dollars as reserves to insure against possible capital flight or financial crisis.

From the U.S. point of view, China’s accumulation of foreign exchange reserves (mostly in dollar-denominated assets) has essentially allowed it to “purchase” trillions of dollars’ worth of Chinese goods largely by printing money without providing any material goods in return. China’s reserve assets, rather than being a part of China’s imperialist wealth, essentially constitute China’s informal tribute to U.S. imperialism by paying for the latter’s “seigniorage privilege.”

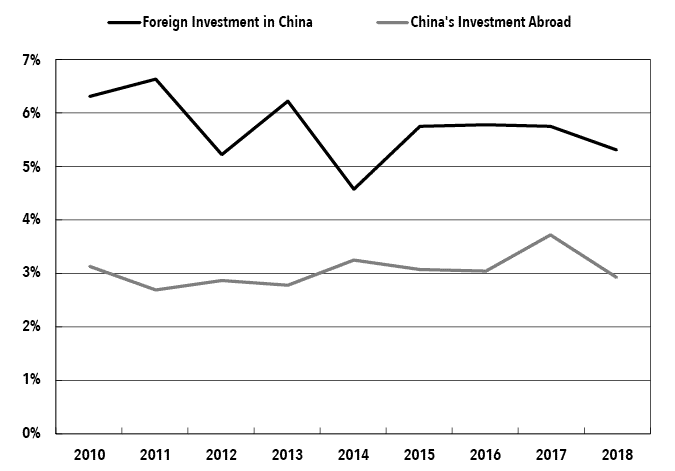

While China’s total overseas assets are greater than its liabilities by $2.13 trillion, China’s investment income received in 2018 was actually smaller than the investment income paid by $61 billion.17 Chart 1 compares the rates of return on China’s total investment overseas with those on foreign investment in China from 2010 to 2018.

Chart 1. Rates of Return on Investment (2010-2018)

Sources: Rates of return are calculated as ratios of investment income to the stock of total investment. China’s overseas investment, foreign investment in China, investment income received and paid are from “The Time-Series Data of International Investment Position of China,” State Administration of Foreign Exchange, People’s Republic of China, March 26, 2021; “The Time-Series Data of Balance of Payments of China,” State Administration of Foreign Exchange, People’s Republic of China, March 26, 2021.

From 2010 to 2018, the rates of return on China’s overseas assets averaged about 3 percent and the rates of return on total foreign investment in China varied mostly in the range of 5 to 6 percent. An average rate of return of about 3 percent on China’s overseas investment obviously does not constitute “superprofits.” Moreover, foreign capitalists in China are able to make about twice as much profit as Chinese capital can make in the rest of the world on a given amount of investment.

On the eve of the First World War, net property income from abroad accounted for 8.6 percent of the British gross national product and total property income accounted for 9.6 percent. It was by observing such massive superprofits that Lenin considered exports of capital to be of “exceptional importance” in the era of imperialism. By comparison, China’s total investment income received in 2018 was $215 billion or 1.6 percent of China’s gross domestic product (GDP) and China’s net investment income from abroad is negative.18

The general pattern of China’s investment abroad can be further revealed by examining where the Chinese investment takes place. China’s total stock of direct investment abroad in 2017 was $1.81 trillion, including $1.14 trillion invested in Asia (63 percent), $43 billion invested in Africa (2.4 percent), $111 billion invested in Europe (6.1 percent), $387 billion invested in Latin America and the Caribbean (21 percent), $87 billion invested in North America (4.8 percent), and $42 billion invested in Australia and New Zealand (2.3 percent).

Within Asia, about $1.04 trillion was invested in Hong Kong, Macao, and Singapore. Hong Kong and Macao are China’s special administrative regions and Singapore is an ethnic-Chinese city-state. About $9 billion was invested in Japan and South Korea. Within Latin America and the Caribbean, $372 billion was invested in the Cayman Islands and British Virgin Islands.19

China’s massive investments in Hong Kong, Macao, Singapore, Cayman Islands, and British Virgin Islands (altogether $1.41 trillion or 78 percent of China’s direct investment abroad) are obviously not intended to exploit abundant natural resources or labor in these cities or islands. Some of China’s investment in Hong Kong is the so-called “round trip investment” to be recycled back to China in order to be registered as “foreign investment” and receive preferential treatments.20 Much of the Chinese investment in these places may simply have to do with money laundering and capital flight. In 2012, Bloomberg reported that Xi Jinping’s family had several real estate properties in Hong Kong with a combined value of £35 million. In 2014, a report by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists further revealed that Xi’s brother-in-law once owned two shell companies based in the British Virgin Islands. China’s investment in these tax havens has more similarities with wealth transfers by corrupt governments in the third world than projects of imperialist plunder. Much of China’s investment in Europe, North America, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand is likely to be of a similar character. Rather than “exploiting” the developed capitalist countries, such capital flight in fact transfers resources from China to the core of the capitalist world system.21

This leaves about $158 billion (8.7 percent of China’s total stock of direct investment abroad or 2.2 percent of China’s total overseas assets) invested in Africa, Latin America, and the rest of Asia. This part of Chinese investment no doubt exploits the peoples in Asia, Africa, and Latin America of their labor and natural resources. But it is a small fraction of China’s total overseas investment and an almost negligible part of the enormous total wealth that Chinese capitalists have accumulated (China’s domestic capital stock is about five times as large as China’s overseas assets). Some Chinese capitalists may be blamed for their imperialist-like behaviors in developing countries, but, on the whole, Chinese capitalism remains nonimperialist.

Unequal Exchange and Global Exploitation

Lenin considered the export of capital to be exceptionally important in the imperialist era. By the mid–twentieth century, Marxist theorists of imperialism already realized that, in the postcolonial era, imperial exploitation of underdeveloped countries mainly took the form of unequal exchange. That is, underdeveloped countries (peripheral capitalist countries) typically export commodities that embody comparatively more labor than the labor embodied in commodities exported by developed capitalist countries (imperialist countries). In the twenty-first century, global outsourcing by transnational corporations based on the massive wage differentials between workers in imperialist and peripheral countries may be seen as a special form of unequal exchange.22

Given the development of the globalized capitalist division of labor and complex interactions of international trade and capital flows, it is difficult (if not impossible) to identify any single country in today’s world to be either a “100 percent” exploiter in its economic relations with the rest of the capitalist world system or “100 percent” exploited. More likely, a country may simultaneously engage in exploiting relations with some countries but have exploited relations with others. Therefore, to identify a country’s position in the capitalist world system, it is important not just to focus on one side of the relations (for example, calling China imperialist simply because China has exported capital). Instead, it is necessary to consider all trade and investment relations involved and find out whether, on the whole, the country receives more surplus value from the rest of the world than it transfers to the rest of the world. On the one hand, if a country receives substantially more surplus value from the rest of the world than it transfers, then the country clearly qualifies as an imperialist country in the sense of being an exploiter country in the capitalist world system. On the other hand, if a country transfers substantially more surplus value to the imperialist countries than it receives from the transfer of the rest of the world, the country would be either a peripheral or a semi-peripheral member of the capitalist world system (depending on further study of the country’s position relative to other peripheral and semi-peripheral countries).

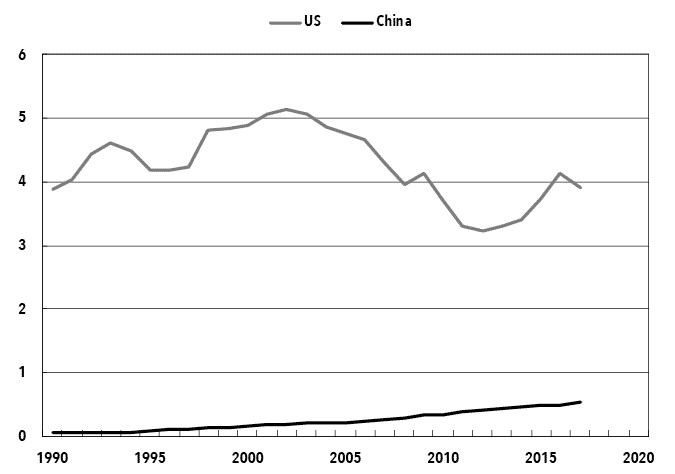

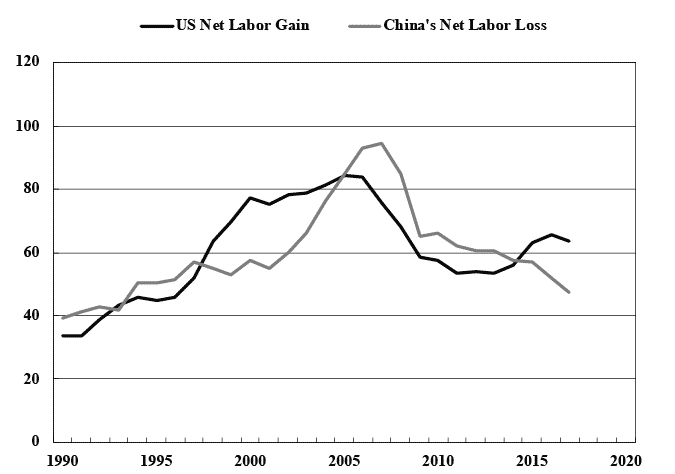

Chart 2 compares the average labor terms of trade of China and the United States. The labor terms of trade is defined as the units of foreign labor that can be exchanged for one unit of domestic labor through trade of exported goods and imported goods of equal market value.

Chart 2. Average Labor Terms of Trade (1990-2017)

Chart 3. Net Labor Transfer (Million Worker-Years, 1990-2017)

Chart 4. China’s Labor Terms of Trade (1990-2017))

China as a Semi-Peripheral Country

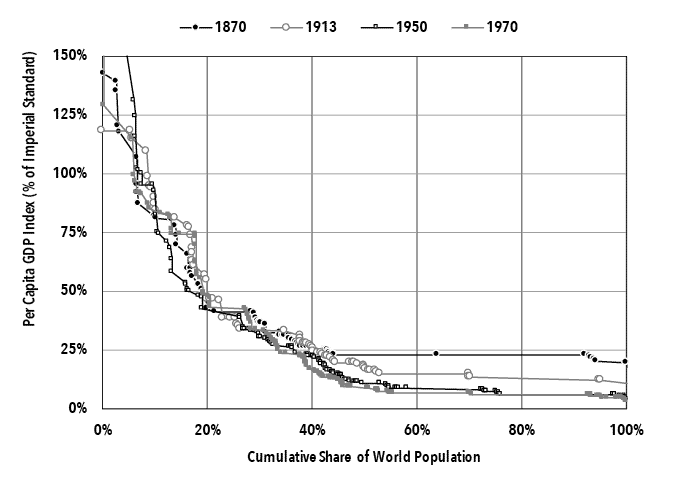

Chart 5. World Hierarchy of Per Capita GDP, 1870-1970

Sources: Angus Maddison, “Statistics on World Population, GDP, and Per Capita GDP, 1–2008 AD,” Groningen Growth & Development Centre, 2010. Per capita GDP is measured by constant 1990 international dollars.

In a study of global inequalities, Giovanni Arrighi used the weighted average per capita gross national product of about a dozen Western capitalist economies that had occupied the top positions of the global hierarchy of wealth. Arrighi referred to these Western capitalist economies as the “organic core” and their average per capita gross national product as the “standard of wealth,” a standard for the rest of the world that helped determine whether a country had “succeeded” or “failed” in the capitalist world system.24

I use a similar concept here. Instead of calculating the average per capita GDP of a dozen Western economies, I focus on four major historical imperialist powers: the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. The four countries were leading imperialist powers in the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth century and have stayed consistently among the wealthiest countries in the capitalist world system since 1870. In this sense, it may be argued that the four countries combined have set the “imperial standard” for the capitalist world system. In Chart 5, the per capita GDP of every country is calculated as an index using the weighted average of the four imperialist countries as 100 (that is, “the imperial standard”).

From 1870 to 1970, world income distribution patterns had remained mostly stable. During those one hundred years, about 60 percent of the world population lived in countries with per capita GDP less than 25 percent of the imperial standard; about 20 percent of the world population lived in countries with per capita GDP between 25 and 50 percent of the imperial standard; and the remaining 20 percent lived in countries with per capita GDP greater than 50 percent of the imperial standard.

Within the top 20 percent of the world population, the most privileged had per capita GDP greater than 75 percent of the imperial standard. From 1870 to 1970, the share of the world population that lived in countries with per capita GDP greater than 75 percent of the imperial standard varied between 10 percent (in 1950) and 17 percent (in 1913). This is a range consistent with the population share of “a handful of exceptionally rich and powerful states” suggested by Lenin.

The United States consistently stayed above the imperial standard from 1870 to 1970. The United Kingdom had a per capita GDP that was 139 percent of the imperial standard in 1870 but its relative per capita GDP declined to 82 percent of the imperial standard by 1970, reflecting the historical decline of British imperialism. French per capita GDP was 82 percent of the imperial standard in 1870 and 77 percent in 1913. German per capita GDP was 80 percent of the imperial standard in 1870 and 81 percent in 1913. The relative positions of both countries fell sharply in 1950, because of the massive destruction of the Second World War. In 1970, French per capita GDP was 87 percent of the imperial standard and German per capita GDP was 83 percent. Thus, with the exception of the period just before and after 1950, French and German per capita GDP stayed above 75 percent of the imperial standard between 1870 and 1970.

It is therefore reasonable to use 75 percent of the imperial standard as the approximate threshold between the core of the capitalist world system and the semi-periphery. It is important to note that this is only an approximate threshold and other important characteristics (such as state strength, degree of political and economic independence, technological sophistication, and so on) also need to be considered when deciding whether a country is a member of the core or simply has a core-like income level. For example, in 1970, among the wealthiest countries were rich oil exporters such as Qatar, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela that clearly do not qualify as core countries.

At the other end of the hierarchy, China and India in 1870 had a per capita GDP just below 25 percent of the imperial standard. India was a British colony and China was a semi-colonial country under the competing influence of several imperialist powers. Both were a part of the periphery in 1870. From 1870 to 1970, the share of the world population that lived in countries with per capita GDP less than 25 percent of the imperial standard increased from 57 percent to 66 percent, suggesting widening global inequalities. I use 25 percent of the imperial standard as the approximate threshold between the periphery and the semi-periphery.

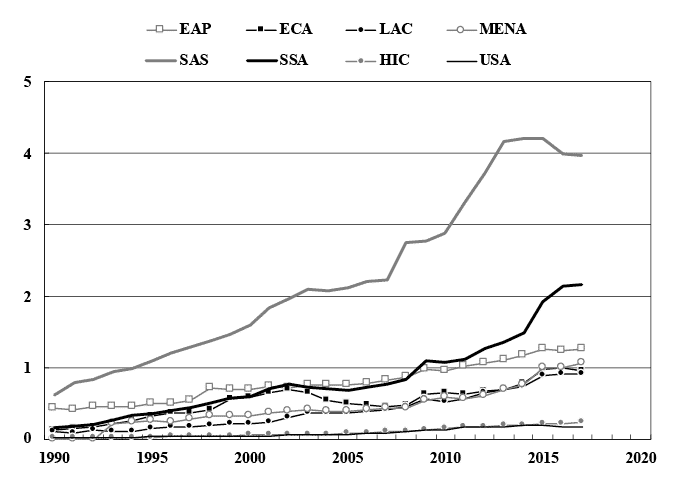

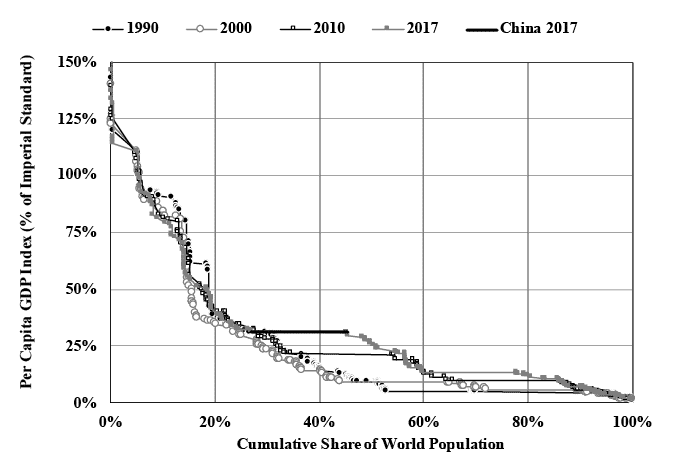

Chart 6 shows the index of per capita GDP of all countries in the world ranked from the highest to the lowest in relation to the countries’ cumulative share of the world population in 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2017.

Chart 6. World Hierarchy of Per Capita GDP, 1990-2017

Table 1 shows the balances of international labor transfer for various parts of the world in 2017.

Table 1. Balances of International Labor Transfer, 2017 (Million Worker-Years)

| Labor Embodied in Exports | Labor Embodied in Imports | Net Labor Loss | Net Labor Gain | |

| China | 91 | 44 | 47 | |

| East Asia and Pacific (ex. China) | 53 | 25 | 28 | |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 36 | 24 | 12 | |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 38 | 26 | 12 | |

| Middle East and North Africa | 16 | 11 | 5 | |

| South Asia | 88 | 23 | 65 | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 31 | 16 | 15 | |

| High Income (ex. U.S.) | 121 | 251 | 130 | |

| United States | 16 | 80 | 64 | |

| Statistical Discrepancies | -10 | -10 | ||

| World | 490 | 490 | 184 | 184 |

Sources: “World Development Indicators,” World Bank, accessed May 31, 2021. All country groups other than the high-income countries refer to low- and middle-income countries. For details of methodology, see Minqi Li, China and the 21st Century Crisis (London: Pluto, 2015), 200–2.

China is the single largest provider of labor embodied in exported goods among all groups of low- and middle-income countries, providing exports that embody about 90 million worker-years annually. But South Asia has recently overtaken China to become the largest source of net labor transfer in the global capitalist economy. In 2017, South Asia suffered a net labor loss of 65 million worker-years. All the low- and middle-income countries combined provided a total net labor transfer of 184 million worker-years in 2017. The United States absorbed about one-third of the surplus value transferred from the low- and middle-income countries; the rest of the high-income countries received about two-thirds. It should be noted that the World Bank definition of high-income countries includes not only all the core capitalist countries but also high-income oil exporters (Saudi Arabia and several small Gulf states), high-income small islands, wealthy cities and city-states (Singapore and China’s special administration regions – Hong Kong and Macao), and a number of relatively well-to-do semi-peripheral countries, such as Chile, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Croatia, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, South Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Uruguay.

If China were to become a core country, then it would cease to be a net provider of surplus value to the capitalist world system and be turned into a net recipient of surplus value from the rest of the world. Assuming that China’s average labor terms of trade rises from the current level of about 0.5 (one unit of Chinese labor exchanges for about half of a unit of foreign labor) to about 2 (one unit of Chinese labor exchanges for about two units of foreign labor, similar to the current average labor terms of trade of the non-U.S. high-income countries), then the total labor embodied in China’s imported goods and services would have to rise to about 180 million worker-years. Rather than providing a net labor transfer of nearly 50 million worker-years, China will have to extract 90 million worker-years from the rest of the world. The total shift of 140 million worker-years represents about three-quarters of the total surplus value currently received by the core and the upper-level semi-periphery from the rest of the world and is roughly comparable to the total net labor transfer currently provided by all the low- and middle-income countries (excluding China).

Thus, if China were to become a core country in the capitalist world system, the existing core countries would have to give up most of the surplus value they are currently extracting from the periphery. It is inconceivable that the core countries would remain economically and politically stable under such a development. Alternatively, the capitalist world system would have to develop new schemes of exploitation that manage to extract 140 million worker-years of additional surplus value from the remaining part of the periphery. It is difficult to see how the exploitation imposed on the periphery can be increased by such a massive extent without causing either rebellion or collapse.

China’s advance into the core would require not only the extraction of hundreds of millions of worker-years from the rest of the world, but also massive amounts of energy resources.

Energy Limits to Economic Growth

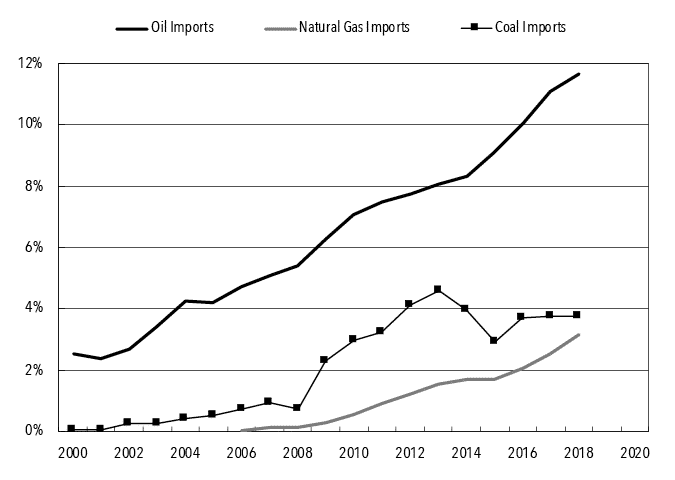

China is now simultaneously the world’s largest importer of oil, natural gas, and coal. Chart 7 shows China’s imports of oil, natural gas, and coal as shares of world production from 2000 to 2018.

Chart 7. Chinese Energy Imports (as a Percent of World Production, 2000-2018)

Sources: BP, Statistical Review of World Energy 2020 (London: BP, 2019). Oil imports are measured by million barrels per day; natural gas imports are measured by billion cubic meters; and coal imports are measured by million metric tons of oil equivalent.

China’s oil imports were 2.5 percent of the world oil production in 2000. By 2018, China’s oil imports surged to 11.7 percent of the world oil production. From 2000 to 2018, the share of Chinese oil imports in the world oil production had increased at an average annual rate of 0.5 percentage points. At this rate, China’s oil imports will need to absorb about one-fifth of the total world oil production by the early 2030s.

China did not import natural gas before 2006. By 2018, China was already the world’s largest natural gas importer and China’s natural gas imports accounted for 3.1 percent of the world’s natural gas production. China’s coal imports peaked at 4.6 percent of the world coal production in 2013 and had stayed just under 4 percent of the world coal production from 2016 to 2018. Will the rest of the world have the capacity to meet China’s insatiable energy demand as the Chinese ruling class aspires to lead China toward its “great rejuvenation”?

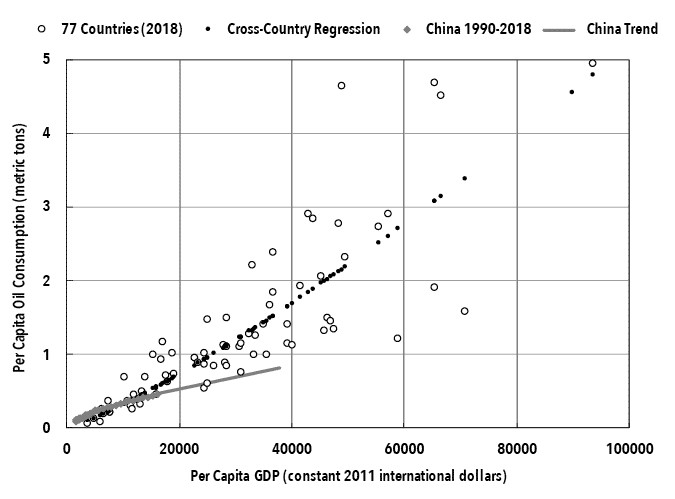

A country’s per capita energy consumption (and especially per capita oil consumption) is closely correlated with its per capita GDP. Chart 8 shows the correlations between per capita GDP (measured by constant 2011 international dollars) and per capita oil consumption (in metric tons) in 2018 for seventy-seven significant energy consuming countries reported by BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy.25

Chart 8. Per Capita GDP and Per Capita Oil Consumption

Sources: Oil consumption data are from BP, Statistical Review of World Energy 2020 (London: BP, 2019). GDP and population data are from “World Development Indicators,” World Bank, accessed May 31, 2021.

A simple cross-country regression finds that a 1 percent increase in per capita GDP is associated with a 1.24 percent increase in per capita oil consumption, with a regression R-square of 0.85 (that is, cross-country variations in per capita GDP can statistically explain 85 percent of the observed variations in per capita oil consumption).

The weighted average per capita GDP of the United States, United Kingdom, France, and Germany in 2018 was $50,312 (in constant 2011 international dollars). This implies that 75 percent of the “imperial standard” is $37,734. Based on the cross-country regression, the implied per capita oil consumption that corresponds to a per capita GDP of $37,734 would be 1.55 metric tons. By comparison, U.S. per capita oil consumption in 2018 was 2.51 metric tons and China’s per capita oil consumption was 543 kilograms. Given China’s population of about 1.4 billion, if China’s per capita oil consumption were to rise to 1.55 metric tons, China’s total oil consumption would have to increase by about 1.4 billion metric tons (on top of China’s existing level of oil consumption). The increased amount is equivalent to 31 percent of world oil production in 2018 or the sum of oil production by the Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq. It is obvious that it is simply impossible for such a massive increase in oil demand to be met under any conceivable circumstances.

Chart 8 also shows the historical evolution of China’s per capita oil consumption from 1990 to 2018 and the historical trend. Interestingly, China’s oil consumption has grown at a less rapid pace than what would be implied by the cross-country regression. A simple regression of the historical relationship between China’s per capita oil consumption and per capita GDP finds that for each 1 percent increase in China’s per capita GDP, China’s per capita oil consumption tends to rise by 0.65 percent. If China’s oil consumption were to grow according to its historical trend, then when China’s per capita GDP rises to $37,734 or reaches 75 percent of the imperial standard, China’s per capita oil consumption should rise to 812 kilograms and China’s total oil consumption should rise to about 1.14 billion metric tons. Compared to China’s oil consumption of 628 million metric tons in 2018, this represents an increase of about 510 million metric tons. As China’s oil production peaked in 2014 and has been in decline, any additional increase in oil consumption will have to be met from imports. An additional oil demand in the amount of 510 million metric tons is larger than the total annual oil exports by either the Russian Federation (which exported 449 million metric tons in 2018) or Saudi Arabia (which exported 424 million metric tons in 2018). Can the world find another Saudi Arabia (and more) to meet China’s additional oil demand corresponding to China’s expected core status?

From 2008 to 2018, the world oil production increased from 4 billion metric tons to 4.47 billion metric tons, or by about 470 million metric tons over a ten-year period. During the same period, U.S. oil production increased from 302 million metric tons to 669 million metric tons and Canada’s oil production increased from 153 million metric tons to 256 million metric tons. The combined increase from U.S. and Canadian oil production was 470 million metric tons, accounting for 100 percent of the world oil production growth over the ten-year period. That is, the entire world oil production growth now depends on the development of U.S. “shale oil” (using environmentally disruptive hydraulic fracturing techniques) and heavily polluting Canadian tar sands. Outside the United States and Canada, the rest of the world’s oil production has stagnated. David Hughes, an independent geologist, argued that the U.S. official energy agency had vastly exaggerated the potential resources of shale oil and the U.S. oil boom would prove to be short-lived.26 If Hughes is correct, world oil production is likely to stagnate (if not enter into permanent decline) beyond the 2020s.

It may be argued that China’s future oil consumption can be reduced substantially through energy efficiency improvement. However, the projections based on China’s historical trend already place China’s future per capita oil consumption at the lower end of the range of cross-country variations in per capita oil consumption given different income levels (see Chart 8). However, the projection is based on the assumption of the imperial standard using 2018 levels of per capita GDP. In the future, if the per capita GDP of four major historical imperialist powers continues to increase (as is likely to be the case), the imperial standard will rise accordingly and bring up the per capita oil consumption level associated with the imperial standard. Any “saving” of oil consumption through energy efficiency improvement is likely to be largely or completely offset by the opposite effect brought about by the rising imperial standard.

China could also attempt to reduce its oil consumption by pursuing a massive program of electrification, replacing oil by domestically produced electricity. In particular, China could try to replace its car fleet with electric vehicles. However, the production of electric vehicles requires large quantities of raw materials, such as lithium and cobalt, that are often produced in politically unstable countries under environmentally damaging conditions. Using the current technology, the production of each electric vehicle requires about ten kilograms of lithium. China is currently producing about twelve million cars a year. Thus, to replace China’s current annual car production by electric vehicles would require the consumption of 120,000 metric tons of lithium annually. World total lithium production in 2018 was only 62,000 metric tons. Therefore, even if China uses up the entire world’s lithium production, it would only be sufficient to replace about one-half of China’s conventional car production.27

China currently has about 140 million passenger cars, or approximately one car for every ten persons.28 If China were to have the same population-car ratio as the United States (two cars for every three persons), China’s total number of cars would need to rise to about one billion. To produce one billion electric cars, China would need a cumulative consumption of ten million metric tons of lithium, using about 72 percent of the world’s current lithium reserves.

Most of China’s oil consumption is not used for cars but for freight transportation and various industrial purposes, which cannot be easily electrified given the current technology and likely technological development in the near term. China’s gasoline consumption for transportation purposes accounts for only about one-tenth of China’s total oil consumption. Therefore, even if in the unlikely event that China turns out to be extremely successful in its effort to promote electric cars, it would at best replace no more than one-tenth of China’s current oil consumption.

Regardless of whether the world can find sufficient energy resources to meet China’s future demand, China’s current energy consumption level is already generating greenhouse gas emissions that are several times the level required for global sustainability.

Climate Crisis and the Exhaustion of the Global Emissions Budget

A scientific consensus has been established that if global average surface temperature rises to two degrees Celsius higher than the preindustrial level, dangerous climate change with catastrophic consequences cannot be avoided. According to James Hansen and his colleagues, global warming by two degrees will lead to the melting of the West Antarctica ice sheets, causing sea levels to rise by five to nine meters over the next fifty to two hundred years. Bangladesh, European lowlands, the U.S. eastern coast, North China plains, and many coastal cities will be submerged. Further increases in global average temperature may eventually lead to runaway warming, turning much of the world unsuitable for human inhabitation. For global ecological sustainability and the long-term survival of human civilization, it is imperative to keep global warming below two degrees Celsius.29

In 2018, the global average surface temperature was 1.12 degrees Celsius higher than the average temperature from 1880 to 1920 (used as a proxy for preindustrial time). The ten-year average temperature from 2009 to 2018 was 1.04 degrees Celsius higher than the preindustrial level.30 To prevent global warming by two degrees Celsius by the end of this century, the world must ensure less than 0.96 degrees Celsius of additional warming.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, cumulative carbon dioxide emissions will largely determine the global mean surface warming over the next century or so. In previous work, I calculated that the remaining global budget for cumulative carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels burning for the rest of the twenty-first century should be no more than 1.4 trillion metric tons. Glen P. Peters and his colleagues used a different set of assumptions and calculated the remaining emissions budget from fossil fuels burning to be only 765 billion metric tons.31

The world population in 2018 was 7.59 billion. Using the more generous 1.4 trillion metric tons as the global emissions budget for the rest of the twenty-first century, an average person in the future is entitled to an average annual emissions budget of about 2.3 metric tons per person per year (1.4 trillion metric tons / 80 years / 7.6 billion people). By comparison, China’s per capita carbon dioxide emissions in 2018 were 6.77 metric tons and the U.S. per capita carbon dioxide emissions were 15.73 metric tons.

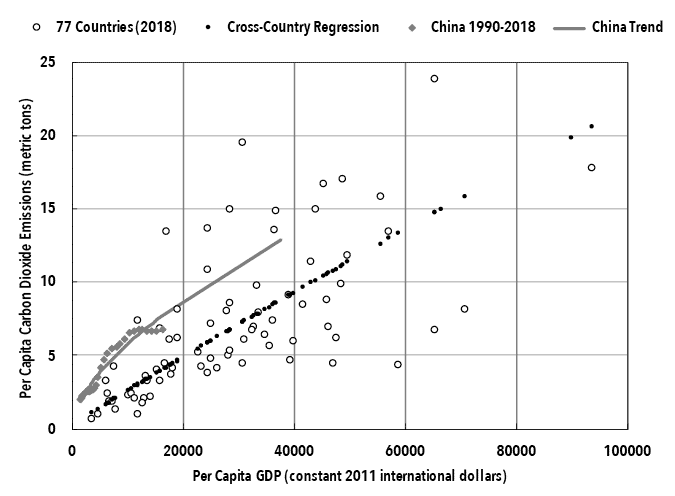

Chart 9 shows the correlations between per capita GDP (measured by constant 2011 international dollars) and per capita carbon dioxide emissions (in metric tons) in 2018 for seventy-seven significant energy consuming countries reported by BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy.32 The figure also shows the historical evolution of China’s per capita carbon dioxide emissions from 1990 to 2018.

Chart 9. Per Capita GDP and Per Capita CO2Emissions

Sources: Carbon dioxide emissions are from BP, Statistical Review of World Energy 2020 (London: BP, 2019). GDP and population data are from “World Development Indicators,” World Bank, accessed May 31, 2021.

From 1990 to 2013, China’s per capita carbon dioxide emissions surged from 2.05 metric tons to 6.81 metric tons. If this trend were to continue, China’s per capita carbon dioxide emissions would rise to 12.85 metric tons when China’s per capita GDP rises to $37,734 (75 percent of the imperial standard). If every person in the world were to generate this level of emissions every year between now and the end of the century, global cumulative emissions over the last eight decades of this century would amount to 7.8 trillion metric tons, leading to 5.5 degrees Celsius of additional warming (using the approximate calculation that every one trillion tons of carbon dioxide emissions would bring about 0.7 degrees Celsius of additional warming).

As China’s energy efficiency improves and China makes efforts to substitute natural gas and renewable energies for coal, China’s per capita carbon dioxide emissions have actually leveled off since 2013. However, as China’s oil and natural gas consumption continues to grow rapidly, China’s per capita emissions may resume growth in the future, though at a slower pace.

China’s current per capita carbon dioxide emissions are substantially above what would be predicted by the cross-country regression given China’s current income level. Using the cross-country regression, if China’s per capita GDP were to rise to $37,734, China’s per capita carbon dioxide emissions should be 8.67 metric tons. If every person in the world were to generate emissions of 8.67 tons every year between now and the end of the century, global cumulative emissions over the last eight decades of this century would amount to 5.3 trillion metric tons, leading to 3.7 degrees Celsius of additional warming. As the global average temperature is already about one degree Celsius higher than the preindustrial level, global warming by the end of the century would be 4.7 degrees Celsius. This will lead to inevitable runaway global warming and reduce the areas suitable for human inhabitation to a small fraction of the earth’s land surface.

Can China reduce its per capita emissions to levels consistent with its climate stabilization obligations without abandoning its ambition to become a part of the core of the capitalist world system?

To meet the climate stabilization obligations, China (as well as every other country) should keep per capita carbon dioxide emissions to below 2.3 metric tons, which is consistent with a per capita GDP of $9,339 based on the cross-country regression (equaling 19 percent of the imperial standard in 2018). In other words, climate stabilization and global ecological sustainability can be accomplished if every country either accepts a massive reduction of per capita income to peripheral levels or stays with the peripheral levels.

Alternatively, China may hope that energy efficiency technology may improve rapidly and consumption of fossil fuels can be mostly substituted by renewable energies so that China can simultaneously accomplish substantial economic growth and rapid reduction of emissions in the future. From 2008 to 2018, world economic output grew at an average annual rate of 3.3 percent and world carbon dioxide emissions grew at an average annual rate of 1.1 percent, implying an average annual reduction rate of emissions intensity of GDP of 2.2 percent. If the world average emissions intensity of GDP continues to fall at this rate in the future, it will take sixty years to reduce the per capita carbon dioxide emissions associated with the per capita GDP of $37,734 from 8.67 metric tons to 2.3 metric tons. But this has not taken into account the offsetting effect of a rising imperial standard in the future. If the weighted average per capita GDP of the four major historical imperialist powers keeps growing by 1 percent a year, then the effective emissions reduction rate relative to the rising imperial standard would be only 1.2 percent. At this rate, it would take 110 years to reduce the per capita carbon dioxide emissions associated with 75 percent of the imperial standard to 2.3 metric tons. But the world simply does not have 110 years to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to stabilize the climate. If the world keeps its current emissions levels (about thirty-four billion metric tons a year), it will take less than twenty years before the world’s remaining emissions budget (required to keep global warming at less than two degrees Celsius) becomes completely exhausted.33

Concluding Remarks

The currently available evidence does not support the argument that China has become an imperialist country in the sense that China belongs to the privileged small minority that exploits the great majority of the world population. On the whole, China continues to have an exploited position in the global capitalist division of labor and transfers more surplus value to the core (historical imperialist countries) than it receives from the periphery. However, China’s per capita GDP has risen to levels substantially above the peripheral income levels and, in term of international labor transfer flows, China has established exploitative relations with nearly half of the world population (including Africa, South Asia, and parts of East Asia). Therefore, China is best considered a semi-peripheral country in the capitalist world system.

The real question is whether China will continue to advance into the core of the capitalist world system and what may be the global implications. Historically, the capitalist world system has been based on the exploitation of the great majority by a small minority that lives in the core or the historical imperialist countries. Given its enormous population, there is no way for China to become a core country without dramatically expanding the population share of the wealthy top layer of the world system. The implied labor extraction (or transfer of surplus value) demanded from the rest of the world would be so large that it is unlikely to be met by the remaining periphery reduced in population size. Moreover, the required energy resources (especially oil) associated with China’s expected core status cannot be realistically satisfied from either future growth of world oil production or conceivable technical change. In the unlikely event that China does advance into the core, the associated greenhouse gas emissions will contribute to rapid exhaustion of the world’s remaining emissions budget, making global warming by less than two degrees Celsius all but impossible.

Several scenarios may evolve in the future. First, China may follow the footsteps of historical semi-peripheral countries. As China’s economic growth continues in the next few years, the growth process may generate various economic and social contradictions (perhaps similar to what happened to Eastern European and Latin American countries in the 1970s and ’80s) and China’s rapid growth will be brought to an end by a major economic crisis that may be followed by political instabilities. If such a scenario emerges, China will then be trapped in the layer of semi-periphery, consistent with the historical laws of motion of the capitalist world system that have so far operated.

The second possible scenario is for China to keep moving up in the global income hierarchy beyond the historical range of most semi-peripheral countries. For example, China’s per capita GDP may rise above 50 percent of the imperial standard and begin to approach 75 percent. If such a scenario does materialize, China’s exploitation of labor and energy resources from the rest of the world may become so massive that China’s exploitation imposes unbearable burdens on peripheral regions such as Africa, South Asia, and parts of East Asia. As a result, general instabilities fall on these regions that could pave the way for either revolutionary transformation or a general collapse of the system. However, China’s massive energy demand may lead to intense rivalry with other major energy importers, causing escalating geopolitical instabilities, with the Chinese economy itself perhaps becoming vulnerable to such instabilities (for example, a revolution in Saudi Arabia).

Finally, there is the unlikely scenario that China somehow “succeeds” in its national project to “catch up” with the West and joins the core of the capitalist world system. In this scenario, the combined energy demand by China and the existing core countries, as well as the enormous greenhouse gas emissions and other pollutants generated by a greatly expanded imperialist core, will completely overwhelm the global ecological system, destroying not only the environment but also any meaningful hope for a sustainable human civilization. It is therefore in the best interest of humanity as well as China that such a scenario does not materialize.

Notes

- ↩ Jeff Desjardins, “China’s Staggering Demand for Commodities,” Visual Capitalist, March 2, 2018.

- ↩ Alexis Okeowo, “China in Africa: The New Imperialists?,” New Yorker, June 12, 2013.

- ↩ Ryan Cooper, “The Looming Threat of Chinese Imperialism,” Week, March 29, 2018.

- ↩ James A. Millward, “Is China a Colonial Power?,” New York Times, May 4, 2018.

- ↩ Jamil Anderlini, “China Is at Risk of Becoming a Colonial Power,” Financial Times, September 19, 2018.

- ↩ Akol Nyok Akol Dok and Bradley A. Thayer, “Takeover Trap: Why Imperialist China Is Invading Africa,” National Interest, July 10, 2019.

- ↩ I. Lenin, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916; repr. Chippendale, Australia: Resistance Books, 1999).

- ↩ Lenin, Imperialism, 92.

- ↩ Anthony Brewer, Marxist Theories of Imperialism: A Critical Survey (New York: Routledge, 1980), 21–23.

- ↩ B. Turner, Is China an Imperialist Country? Considerations and Evidence(Montreal: Kersplebedeb, 2015).

- ↩ David Harvey, “David Harvey’s Response to John Smith on Imperialism,” Radical Political Economy (blog), February 23, 2018.

- ↩ Hua Shi, “Imperialism, Ultra-Imperialism, and the Rise of China” [in Chinese], Jiliu Wang, September 19, 2017.

- ↩ Lenin, Imperialism, 39, 63–64.

- ↩ Lenin, Imperialism, 92, 101, 104.

- ↩ Lenin, Imperialism, 30–31.

- ↩ “The Time-Series Data of International Investment Position of China,” State Administration of Foreign Exchange, People’s Republic of China, March 26, 2021.

- ↩ “The Time-Series Data of Balance of Payments of China,” State Administration of Foreign Exchange, People’s Republic of China, March 26, 2021.

- ↩ Brian R. Mitchell, British Historical Statistics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 829, 872.

- ↩ “Annual National Data,” National Bureau of Statistics, People’s Republic of China, accessed May 31, 2021.

- ↩ Natasha Khan and Yasufumi Saito, “Money Helps Explain Why China Values Hong Kong,” Wall Street Journal, October 23, 2019.

- ↩ “Xi Jinping Millionaire Relations Reveal Fortunes of Elite,” Bloomberg, June 29, 2012; Dexter Roberts, “China’s Elite Wealth in Offshore Tax Havens, Leaked Files Show,” Bloomberg, January 2, 2014.

- ↩ Arghiri Emmanuel, Unequal Exchange: A Study of the Imperialism of Trade (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1972); Samir Amin, Unequal Development: An Essay on the Social Formations of Peripheral Capitalism(New York: Monthly Review Press, 1976); Immanuel Wallerstein, The Capitalist World-Economy: Essays by Immanuel Wallerstein (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), 71; John Smith, Imperialism in the Twenty-First Century: Globalization, Super-Exploitation, and Capitalism’s Final Crisis (New York, Monthly Review Press, 2016), 9–38, 187–223, 232–33.

- ↩ Immanuel Wallerstein, World-System Analysis: An Introduction (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 23–41.

- ↩ Giovanni Arrighi, “World Income Inequalities and the Future of Socialism,” New Left Review 189 (1991): 39–66.

- ↩ BP, Statistical Review of World Energy 2020 (London: BP, 2019).

- ↩ David Hughes, Shale Reality Check: Drilling into the U.S. Government’s Rosy Projections for Shale Gas & Tight Oil Production Through 2050(Corvallis: Post Carbon Institute, 2018).

- ↩ Tam Hunt, “Is There Enough Lithium to Maintain the Growth of the Lithium-Ion Battery Market?,” Green Tech Media, June 2, 2015; “Annual National Data”; BP, Statistical Review of World Energy 2020.

- ↩ “Annual National Data.”

- ↩ James Hansen et al., “Ice Melt, Sea Level Rise and Superstorms: Evidence from Paleoclimate Data, Climate Modeling, and Modern Observations that 2°C Global Warming Could Be Dangerous,” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 16, no. 6 (2016): 3761–812.

- ↩ “GISS Surface Temperature Analysis,” National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Goddard Institute for Space Studies, accessed May 31, 2021.

- ↩ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, “Summary for Policymakers,” in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, ed. T. F. Stocker et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 27–29; Minqi Li, “Global Carbon Dioxide Emissions and Climate Change 2018–2100,” Peak Oil Barrel, November 20, 2018; Glen P. Peters, Robbie M. Andrew, Susan Solomon, and Pierre Friedlingstein, “Measuring a Fair and Ambitious Climate Agreement Using Cumulative Emissions,” Environmental Research Letters 10, no. 10 (2015): 105004–12.

- ↩ BP, Statistical Review of World Energy 2020.

- ↩ “Carbon Countdown Clock: How Much of the World’s Carbon Budget Have We Spent,” Guardian, accessed June 1, 2021.

2021, Volume 73, Issue 3 (July-August 2021)

A pedestrian walks past a McDonald’s outlet in Yichang, Hubei province. Credit: Xinhua, “China expanding agricultural cooperation with Belt and Road countries,” China Daily, March 29, 2021.

Minqi Li is a professor of economics at the University of Utah. Li can be reached at minqi.li [at] economics.utah.edu.

Subscribe to the Monthly Review e-newsletter (max of 1-3 per month).

COMMENTS