Deepak Adhikari : The old school building in Puente América has seen better days. Once a place where the children of the tiny Colombian hamlet would come to learn their lessons, today it looks like little more than an abandoned ruin.

But inside, its walls tell a different story.

A reporter who visited in 2015 found the former classrooms covered with messages in Hindi, English, Nepalese, Bengali, and Arabic, written by migrants who had taken shelter there during their long journeys to North America.

Some wrote their names on the flimsy wall: “Alhaji Abass from Mamobi,” “Bilal Warrakh, Pakistan,” “Zakari Ganiou le Beninois.” Others wrote prayers for help, calling on “almighty Allah [to] guide us.”

One man from Comilla in Bangladesh, who called himself Faiz Almed Jewel, left a warning to other migrants who may pass through after him.

“Our destination is U.S.A.,” he wrote in broken English. “When I took this decision that time, I didn’t know it’s a riskable way. This is the especially request to my brother: don’t believe to broker. They are cheaters. They are liars. Really it’s very danger just to ride the speed boats across the jungle. Finally just pray for us for safe journey. We also pray for you.”

Puente América, just 25 kilometers from the border with Panama, was a resting point for migrants making their way illegally to the United States or Canada. The next stage is a dangerous trip through the jungle that can take several days, sometimes on boats and sometimes by foot through several communities in the Darién Gap until they reach Yavisa, in Panama, before continuing north.

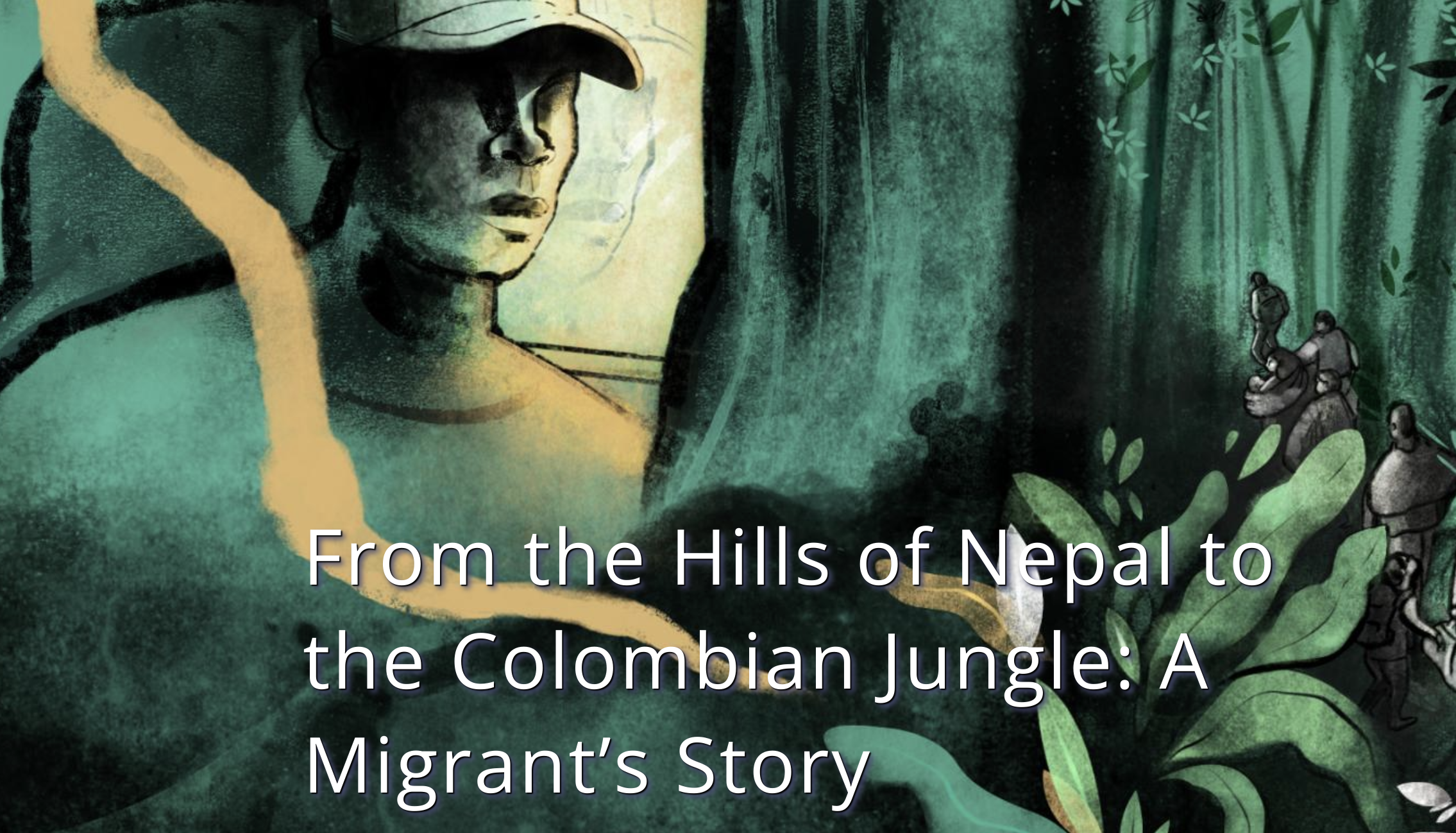

For many of the migrants, this is just one small leg of an odyssey that has already brought them thousands of kilometers from Africa or Asia. Last year, a Nepalese reporter tracked down one man who had written his name in Puente América’s old schoolhouse to learn more about his gruelling six-month journey from Nepal to the U.S.

He was contacted several times, but didn’t answer, so we have referred to him by a pseudonym. But interviews with his friends, family and experts give a glimpse of what it took for him — and many others like him — to go in search of a better life.

‘A Matter of Life and Death’

Ramesh left his home in Kushma, a small town nestled in the rolling hills of Nepal’s Gandaki province, in October 2014.

It was his second time embarking on a long journey in search of better opportunities. He had previously spent six years as a migrant worker in South Korea, before returning home in 2011 and getting married. He even built a house on a plot of land in Kushma given to him by his father, intending to settle down close to home. But his marriage abruptly broke down and he got itchy feet again.

“One by one, his friends left for America. They returned with money. I think he wanted to go after seeing that,” recalled his mother Mithu, sitting on the stairs of the house her son built before he left.

“He would tell me he had big dreams and wanted to go to big countries,” the 69-year-old said. She recalled him vowing, “No matter what, I want to reach America.”

To raise the money for his journey, Ramesh turned to local moneylenders, who gave him the cash at a crippling 18 percent interest. The entire trip cost him 5 million Nepali rupees (US$48,500), a fortune for him and his family.

But his cousin Surya said he convinced them it was worth it because of the possibilities that lay ahead in the United States.

“His expenses were very high, but he didn’t have any source of income. So he decided to go to the U.S.,” he said. “I think he still owes around 1.2 million rupees to the moneylenders.”

Credit: Deepak AdhikariParbat district, where Kushma is located, has emerged as a center for people smuggling to the U.S.

Ramesh is not alone. A local social worker, who asked not to be named to protect their job, said around 500 people have migrated from Kushma to the U.S. since 2000, out of a population of around 10,000. In one neighborhood alone, 27 men from eight families have made the dangerous journey, known locally as “Tallo Bato” (meaning “Lower Road”).

Many turn to local smugglers, who the social worker says then feed them into larger smuggling networks run by kingpins in the capital Kathmandu and New Delhi in India. Ishwar Babu Karki, head of the Anti-Trafficking Unit of Nepal’s police, said Parbat district, where Kushma is located, is among a dozen in midwestern Nepal that have emerged as centers for human smuggling to the U.S.

“Around eight to 10 traffickers operate here. Each has trafficked from a few dozen to about 200 migrants,” said the social worker, adding that the trade remains clandestine because “first, it’s a close-knit society and second, the traffickers may have sent one of their family members to the U.S. Everything remains a secret despite it being so pervasive.”

Law enforcement officers in Kathmandu estimated in January there were 5,000 Nepalese on their way to the United States via Latin America at that time, fleeing unemployment, poverty, and rampant corruption at home.

“Trafficking is now one of the gravest crimes facing us in Nepal. It’s so serious that some international airlines sometimes refuse to board a Nepali in their planes,” said deputy superintendent of police Narahari Regmi.

“We have paid a heavy price due to people smuggling.”

Through the Jungle

By March 2015, the man we are calling Ramesh had reached the old schoolhouse in Puente América. One of his friends told OCCRP’s partner The Confluence Media that to get there he had flown from India to Thailand, then onwards to Russia, Spain, and Brazil. From there, he travelled overland to Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia.

Ramesh did not respond to requests for an interview about his experiences. But a friend and neighbor in Kushma, Nabin, who travelled the same route in 2018, said crossing the jungle between Colombia and Panama was one of the hardest points of his journey.

It took him and his group eight days to make the gruelling 160-kilometer trek on foot. Along the way, he saw a corpse and an Indian man with a broken leg, left stranded in the jungle. He was robbed by armed men and forced to hand over his clothes and shoes.

“The jungle was so wet that you couldn’t walk without wearing rubber boots. It was so dense that I couldn’t see [the] sky for a whole week,” he said.

“If you fell ill and didn’t have any medicines, your fellow travelers left you to die alone. We feared death, arrest and robbery. We subsisted on biscuits, chocolates, and water.”

According to Nabin, after making the crossing, Ramesh continued to Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico. He was robbed in Central America. He was arrested in Mexico. He became sick. Then, after paying another 500,000 rupees, he was finally smuggled across the U.S. border, six months after he left Nepal.

In the first years after he arrived, Ramesh worked at department stores in Baltimore, where his mother said he was again robbed several times. About a year ago, he moved to New Jersey.

His social media posts appear to show him living the American dream. In a photo on Facebook he poses with a New York skyscraper in the background. Pictures on Instagram show him posing under cherry blossoms, barbecuing, or strolling along beaches.

The social worker in Kushma said migrants who manage to make it to the U.S. like Ramesh are seen as success stories back home.

“The family builds a cement and concrete house from the money [sent by the migrant],” he said. “They send their children to private English schools. They buy new cars and go on vacations.”

Others, such as Kushma jewelry shop owner Binod Pokharel, see it differently. “It takes you three to four years to pay back the debts incurred after the trip,” he said. “It’s the traffickers and local money lenders who have profited from this business, not the migrants.”

After fighting his case in immigration courts for several years, Ramesh recently received a U.S. green card and is now planning a trip back to Nepal in the fall, according to his friend Nabin.

Back in Kushma, his mother longs to see him.

“He went through a lot of hardship. He’s everything I have in life. He’s my only child,” she said. “I would have liked him to stay with me in my old days.”

9 July 2020

Additional reporting by Nathan Jaccard (OCCRP) and Jose Guarnizo (Revista Semana).

COMMENTS